Big Break Ride the Waves - that

7 of the world's scariest waves to surf

Big waves mean big adventure. After all, that's one of the reasons Red Bull Cape Fear exists. Along with Shipstern Bluff (where Cape Fear ran in 2020), we thought we'd take a look at some of the other fearsome, mega-sized waves around the planet – the kind that'll chew you up and (hopefully) spit you out.

Ours – Sydney's fearsome locals-only wave

Location: Sydney, Australia

Fear factor: 8

Can you ride it: Almost definitely not

The reason this beast is called 'Ours' is because notorious Australian surf gang the Bra Boys claims ownership of the mean slab in Sydney's Botany Bay. While it was the site of the 2014 Red Bull Cape Fear contest, it's pretty much off-limits for any normal surfer and with good reason – it breaks onto shallow reef just a few feet from the rocks. Gulp.

Mavericks – mainland America's premiere big wave

Location: Half Moon Bay, California, USA

Fear factor: 9

Can you ride it: If you don't mind freezing water and looming rocks.

The story goes that local Jeff Clark surfed Mavericks for years before anyone decided to join him. But once they did the rush was on. Beginning in the 1990s, Mavericks catapulted to the top of the big wave surfing world's radar. Later that decade, waves like Maui's Jaws and Tahiti's Teahupo'o stole a bit of Mavericks spotlight. In the 2000s, it was Nazaré. Despite the competition, though, Maverick' remains a point of pilgrimage for aspiring and veteran big wave surfers alike.

Teahupo'o – the below-sea-level beast

Location: Tahiti

Fear factor: 9

Can you ride it? Not likely

Teahupo'o, often known as 'Chopes', is most likely the world's most famous wave. How scary is it? The name is loosely translated as 'to sever the head' or 'place of skulls'.

How does it work? The ocean approaching the reef is incredibly deep, but the reef itself is very shallow. On a big swell, water is pulled off the reef and then quickly re-deposited back on it. Hopefully without you.

Pipeline – the world's deadliest wave

Location: North Shore, Oahu, Hawaii

Fear factor: 8

Can you ride it? If you can snag one from the local pack.

For a while in the early part of the 20th century, both local and visiting surfers to Oahu's North Shore didn't consider Pipeline surfable. It broke fast, hollow and so steep that its walls appeared to be inverted. Fitting the surfboard of the day – huge, 10-foot-plus things – seemed, and pretty much was, impossible.

Guys like Phil Edwards and Gerry Lopez gave it a go anyway, and as surfboards became shorter, lighter, and more high-tech, Pipeline became the Mecca for tube riding. It's danger however has never ceased. To date, it's considered the world's deadliest wave and it remains the ultimate proving ground for surfers.

Nazaré – Europe's mega wave main stage

Location: Nazaré, Portugal

Fear factor: 9

Can you ride it? If you're brave enough, maybe

Brought to worldwide attention when Hawaiian hellman Garrett McNamara picked off a massive bomb that measured 24m from trough to crest, Nazaré is now Europe's biggest big-wave attraction. Easy viewing from the cliff means that any time the wave breaks, the show is on.

Jaws – the original tow wave

Location: Maui, Hawaii

Fear factor: 6

Can you ride it: Maybe...

The world's mega wave was discovered on the North Coast of Maui by windsurfers in the 1990s. Well before big wave surfing got where it was today, fearless waterman like Dave Kalama and Laird Hamilton windsurfed upwind from Ho'okipa Beach Park to score bombs at what locals called Pe'ahi.

Nicknaming the break 'Jaws', it quickly gained notoriety as tow-surfers began to tackle it on glassy days. These days, very few waves go unridden at Jaws, as any winter swell brings a crowd of wave riders waiting to test their mettle.

Shipstern Bluff – meet the mutant

Location: Tasmania, Australia

Fear factor: 10

Can you ride it: Take our advice and skip this one

If the first peak of big wave riding was tow surfing, followed by paddling in to monsters on big-wave guns, then we're officially in the 'slab' era – where performance surfing is defined by the brave souls willing to explore double-up lips, vertical drops and everything in between. One of the most famous examples? Shipstern Bluff, seen above, where Mick Fanning is dropping into a bone-cruncher.

Stay up to date on Red Bull Cape Fear right here.

Where to Watch the Biggest Waves Break

![]()

Giant counterclockwise cyclones in the Gulf of Alaska generate huge swells that manifest, finally, as the things surfers dream of. This giant wave is breaking at Jaws, a legendary site on Maui. Photo courtesy of Flickr user Jeff Rowley.

The start of the northern meteorological winter on December 1 will bring with it short days of darkness, blistering cold and frigid blizzards. For many people, this is the dreariest time of the year. But for a small niche of water-happy athletes, winter is a time to play, as ferocious storms send rippling rings of energy outward through the ocean. By the time they reach distant shores, these swells have matured into clean, polished waves that barrel in with a cold and ceaseless military rhythm; they touch bottom, slow, build and, finally, collapse in spectacular curls and thundering white water. These are the things of dreams for surfers, many of whom travel the planet, pursuing giant breakers. And surfers aren’t the only ones with their eyes on the water—for surfing has become a popular spectator sport. At many famed breaks, bluffs on the shore provide fans with thrilling views of the action. The waves alone are awesome—so powerful they may seem to shake the earth. But when a tiny human figure on a board as flimsy as a matchstick appears on the face of that incoming giant, zigzagging forward as the wave curls overhead and threatens to crush him, spines tingle, hands come together in prayer, and jaws drop. Whether you like the water or not, big-wave surfing is one of the most thrilling shows on the planet.

The birth of big-wave surfing was an incremental process that began in the 1930s and ’40s in Hawaii, especially along the north-facing shores of the islands. Here, 15-foot waves were once considered giants, and anything much bigger just eye candy. But wave at a time, surfers stoked up their courage and ambition. They surfed on bigger days, used lighter and lighter boards that allowed swifter paddling and hunted for breaks that consistently produced monsters. One by one, big-wave spots were cataloged, named and ranked, and wave at a time, records were set. In November 1957, big-wave pioneer Greg Noll rode an estimated 25-footer in Waimea Bay, Oahu. In 1969, Noll surfed what was probably a 30-plus-footer, but no verified photos exist of the wave, and thus no means of determining its height. Fast-forwarding a few decades, Mike Parsons caught a 66-foot breaker in 2001 at Cortes Bank, 115 miles off San Diego, where a seamount rises to within three feet of the surface. In 2008, Parsons was back at the same place and caught a 77-footer. But Garrett McNamara outdid Parsons and set the current record in November 2011, when he rode a 78-foot wave off the coast of Portugal, at the town of Nazare.

In the 1990s, the advent of “tow-in” surfing using jet skis allowed surfers to consistently access huge waves that otherwise would have been out of reach. Photo courtesy of Flickr user Michael Dawes.

But these later records may not have been possible without the assistance of jet skis, which have become a common and controversial element in the pursuit of giant waves. The vehicles first began appearing in the surf during big-wave events in the early 1990s, and for all their noise and stench, their appeal was undeniable: Jet skis made it possible to access waves 40 feet and bigger, and whose scale had previously been too grand for most unassisted surfers to reach by paddling. Though tow-in surfing has given a boost to the record books, it has also heightened the danger of surfing, and many surfers have died in big waves they might never have attempted without jet-ski assistance. Not surprisingly, many surfers have rejected tow-in surfing as an affront to the purity of their relationship with waves—and they still manage to catch monsters. In March 2011, Shane Dorian rode a 57-foot breaker at the famed Jaws break in Maui, unassisted by a belching two-stroke engine. But many big-wave riders fully endorse tow-in surfing as a natural evolution of the sport. Surfing supertstar Laird Hamilton has even blown off purists who continue to paddle after big waves without jet skis as “moving backward.” Anyway, in a sport that relies heavily on satellite imagery, Internet swell forecasts and red-eye flights to Honolulu, are we really complaining about a little high-tech assistance?

For those wishing merely to watch big waves and the competitors that gather to ride them, all that is needed is a picnic blanket and binoculars—and perhaps some help from this swell forecast website. Following are some superb sites to watch surfers catch the biggest breakers in the world this winter.

Waimea Bay, North Shore of Oahu. Big-wave surfing was born here, largely fueled by the fearless vision of Greg Noll in the 1950s. The definition of “big” for extreme surfers has grown since the early days, yet Waimea still holds its own. Fifty-foot waves can occur here—events that chase all but the best wave riders from the water. When conditions allow, elite surfers participate in the recurring Quicksilver Eddie Aikau Invitational. Spectators teem on the shore during big-swell periods, and while surfers may fight for their ride, you may have to fight for your view. Get there early.

Jaws, North Shore of Maui. Also known as Peahi, Jaws produces some of the most feared and attractive waves on earth. The break—where 50-footers and bigger appear almost every year—is almost strictly a tow-in site, but rebel paddle-by-hand surfers do business here, too. Twenty-one pros have been invited to convene at Jaws this winter for a paddle-in competition sometime between December 7 and March 15. Spectators are afforded a great view of the action on a high nearby bluff. But go early, as hundreds will be in line for the best viewing points. Also, bring binoculars, as the breakers crash almost a mile offshore.

When the surf’s up, crowds gather on the coastal bluffs to watch at Mavericks, near San Francisco. Photo courtesy of Flickr user emilychang.

Mavericks, Half Moon Bay, California. Mavericks gained its reputation in the 1980s and ’90s, during the revival of big-wave surfing, which lost some popularity in the 1970s. Named for a German Shepherd named Maverick who took a surgy swim here in 1961, the site (which gained an “s” but never an official apostrophe) generates some of the biggest surfable waves in the world. Today, surfing competitions, like the Mavericks Big Wave Contest and the Mavericks Invitational, are held each year. The waves of Mavericks crash on a vicious reef, making them predictable (sandy bottoms will shift and change the wave form) but nonetheless hazardous. One of the best surfers of his time, Mark Foo died here in 1994 when his ankle leash is believed to have snagged on the bottom. Later, the waves claimed the life of Hawaiian surfing star Sion Milosky. A high bluff above the beach offers a view of the action. As at Jaws, bring binoculars.

Murky, frigid water breaks in 40- and 50-foot waves every year during periods of high swell at Mavericks. Photo courtesy of Flickr user rickbucich.

Ghost Trees, Monterey Peninsula, California. This break hits peak form under the same swell conditions that get things roaring at Mavericks, just a three-hour drive north. Ghost Trees is a relatively new attraction for big-wave riders. Veteran surfer Don Curry says he first saw it surfed in 1974. Decades would pass before it became famous, and before it killed pro surfer (and a pioneer of nearby Mavericks) Peter Davi in 2007. For surfing spectators, there are few places quite like Ghost Trees. The waves, which can hit 50 feet and more, break just a football field’s length from shore.

Mullaghmore Head, Ireland. Far from the classic Pacific shores of big-wave legend and history, Mullaghmore Head comes alive during winter storms in the North Atlantic. The location produces waves big enough that surfing here has become primarily a jet ski-assisted game. In fact, the event period for the Billabong Tow-In Session at Mullaghmore began on November 1 and will run through February 2013. Just how big is Mullaghmore Head? On March 8, 2012, the waves here reached 50 feet, as determined by satellite measurements. A grassy headland provides an elevated platform from which to see the show. Bundle up if you go, and expect cold, blustery conditions.

Other big wave breaks:

Teahupoo, Tahiti. This coveted break blooms with big swells from the Southern Ocean—usually during the southern winter. Teahupoo is famed for its classic tube breakers.

Shipsterns Bluff, Tasmania. Watch for this point’s giants to break from June through September.

Punta de Lobos, Chile. Channeling the energy of the Southern Ocean into huge but glassy curlers, Punta de Lobos breaks at its best in March and April.

Todos Santos Island, Baja California, Mexico. Todos Santos Island features several well-known breaks, but “Killers” is the biggest and baddest. The surf usually peaks in the northern winter.

There is another sort of wave that thrills tourists and spectators: the tidal bore. These moon-induced phenomena occur with regularity at particular locations around the world. The most spectacular to see include the tidal bores of Hangzhou Bay, China, and Araguari, Brazil—each of which has become a popular surfing event.

Recommended Videos

WATCH: Surfers Ride Towering Waves In Portugal

Brazilian surfer Carlos Burle rides a big wave at the Praia do Norte, north beach, at the fishing village of Nazaré in Portugal's Atlantic coast on Monday. Miguel Barreira/AP hide caption

Brazilian surfer Carlos Burle rides a big wave at the Praia do Norte, north beach, at the fishing village of Nazaré in Portugal's Atlantic coast on Monday.

Miguel Barreira/APHere we go again: As a massive storm brings hurricane force winds through Western Europe, surfers in Nazaré, Portugal were taking advantage of monster waves, triggering rumors of record-breaking rides.

As we've reported, if there is a place to break the record for riding the tallest wave, it's in Nazaré. Back in January, when there were rumors of record-breaking rides, Scott reported that a deep, undersea canyon points massive waves toward the town.

The videos emerging from what happened at Nazaré on Monday are spectacular:

The Guardian reports that British surfer Andrew Cotton and the Brazilian Carlos Burle are claiming that they have taken advantage of the perfect conditions to break the 78-foot record set by American Garrett McNamara in Nazaré back in November of 2011.

"They were absolutely giant waves," Cotton told The Guardian. "I don't know how you would even begin to measure them. It was really exciting, a big day."

The Guardian adds that back in 2011, Cotton towed McNamara on a jet ski to the record-breaking wave. On Monday, McNamara towed Cotton to what could be his historic ride.

As Scott explained, measuring is an imperfect science. The Guardian says "the record will be announced in May next year, at the Billabong XXL awards."

Learn how to read waves and anticipate how they will break

“How do I know if the wave is a right or a left”? “How can I know when a wave is going to break”? “What is a closeout”? These are very common questions we get from our travellers.

Reading waves itself could be considered an art. As you progress from a beginner to an intermediate, then to an advanced surfer, your capacity to read and anticipate waves will slowly increase. Take into consideration it’s not something you will master quickly. Reading waves better mostly comes by spending loads of hours in the ocean. This is why even after a few years of surfing, you might see local surfers paddling for a wave way before you even noticed a lump!

This being said, here are the most important basics to help you get started on your next surf session.

1 . How a wave breaks: Rights, Lefts, A-Frames & Closeouts

When you see a lump on the horizon, you know that the lump will eventually transform into a wave as it gets closer to the shore. This wave may break into different shapes, but most waves can be categorized either as a right, a left, an a-frame or a closeout.

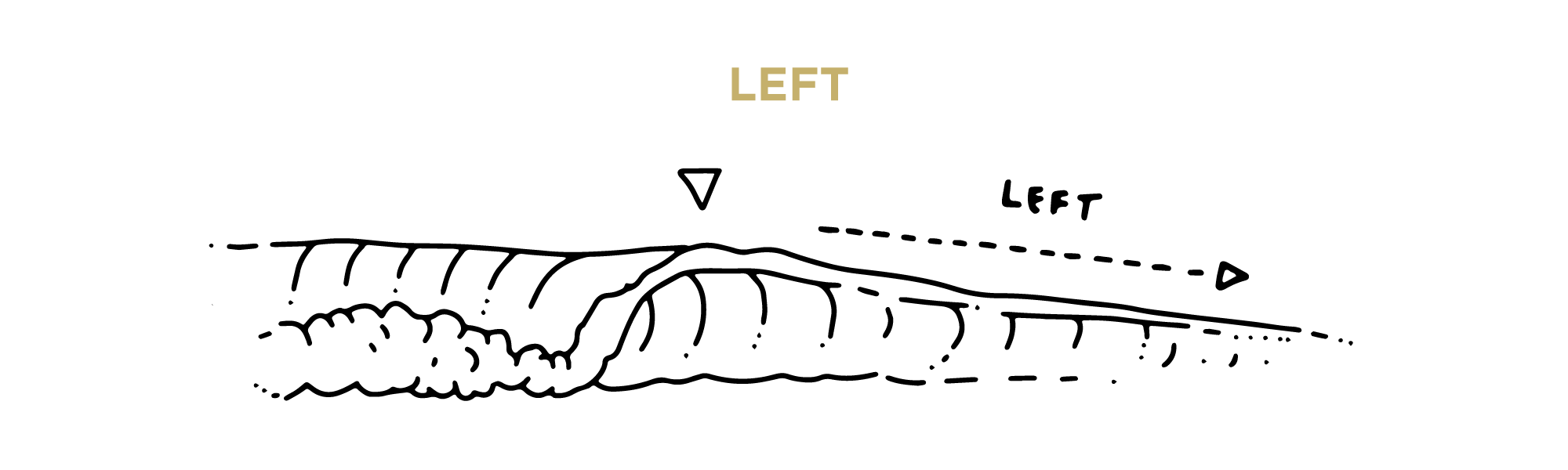

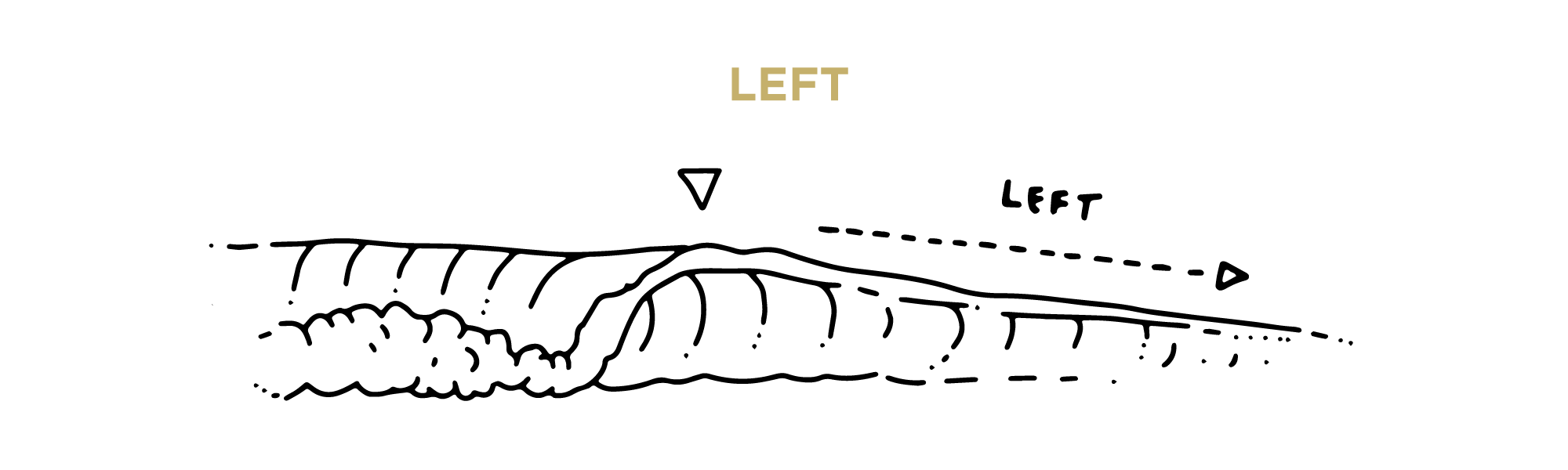

A Left

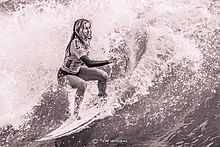

A wave that breaks (or “peels”) to the left, from the vantage of the surfer riding the wave. If you are looking from the beach, facing the ocean, the wave will break towards the right from your perspective. To avoid confusion, surfers always identify wave directions according to the surfer’s perspective: the surfer above is following the wave to his left, this wave is called a “left”.

On the above picture, the Surfer is riding a “left”.

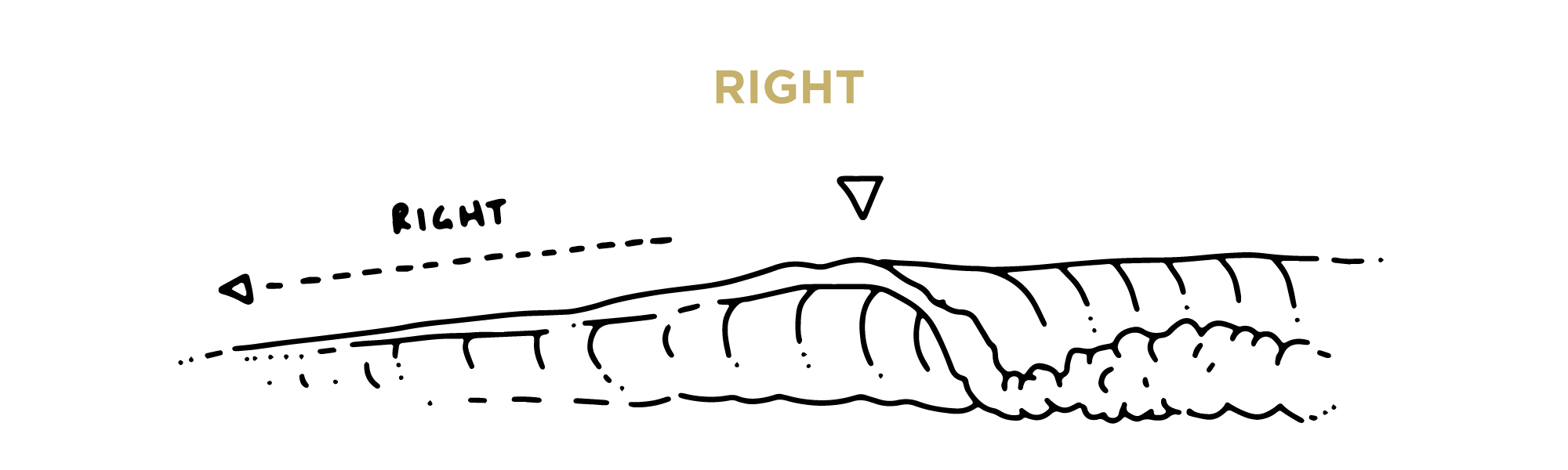

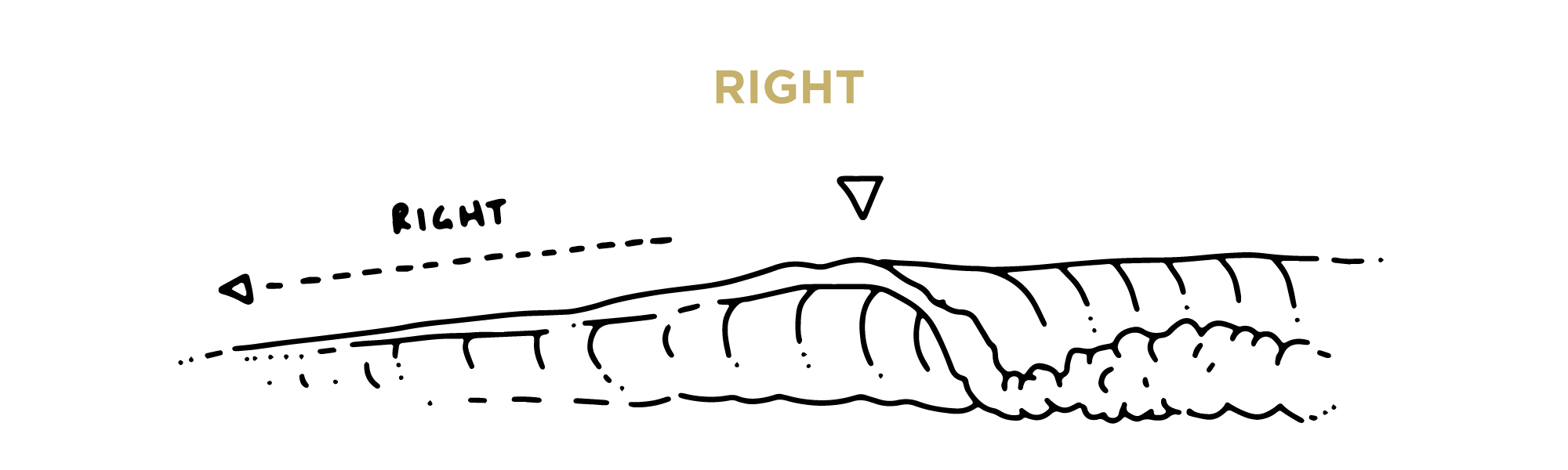

A Right

A wave that breaks to the right from the vantage of the surfer riding the wave. For people looking from the beach, the wave will be breaking to the left from their position.

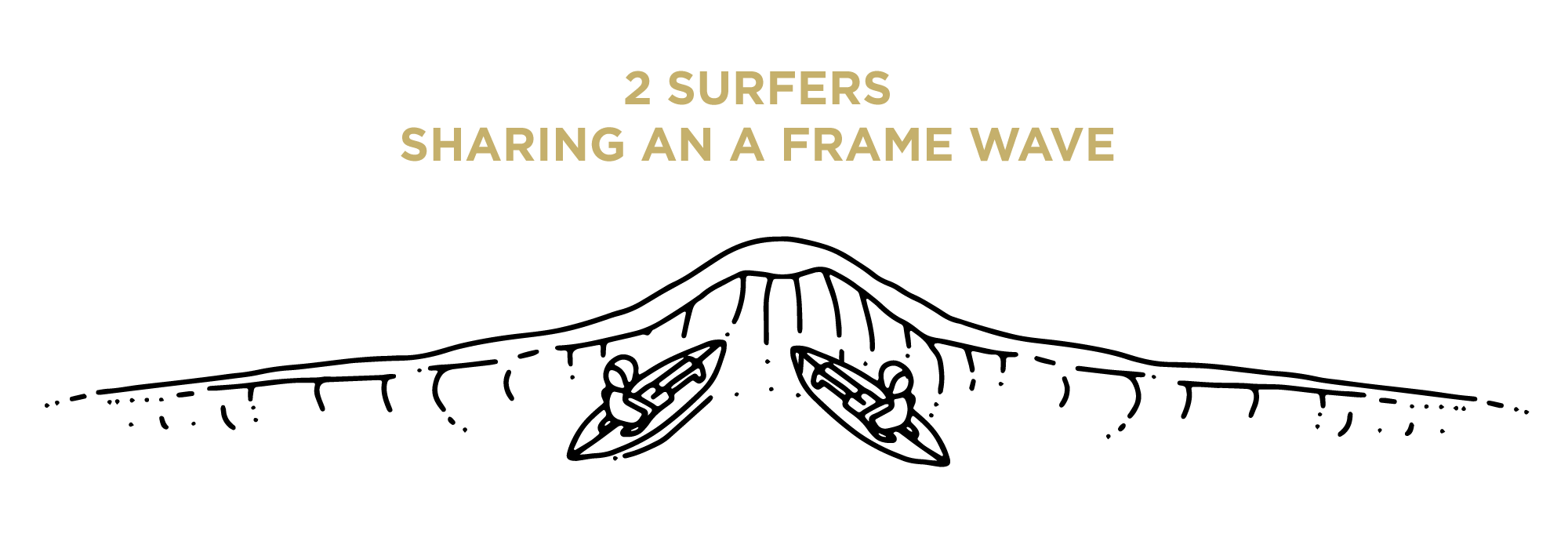

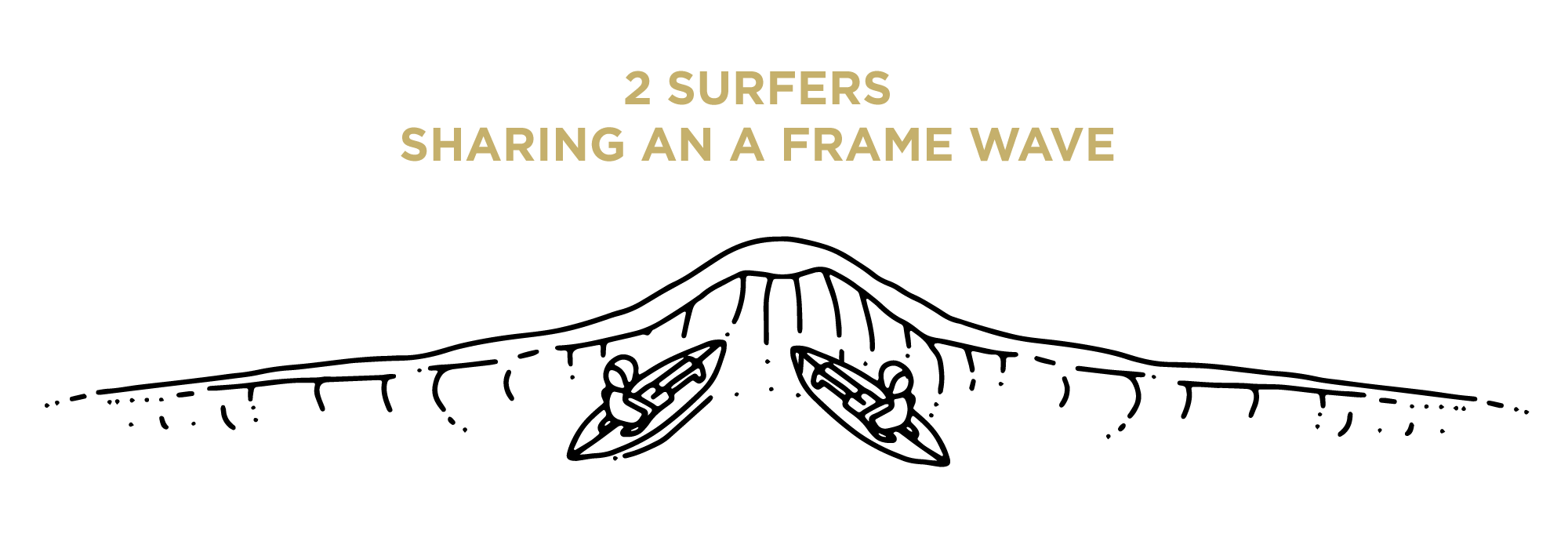

An A Frame

A “peak-shaped” wave, with both right and left shoulders. These waves are great since it doubles the number of rides: 2 surfers can catch the same wave, going in opposite directions (one going right, the other going left).

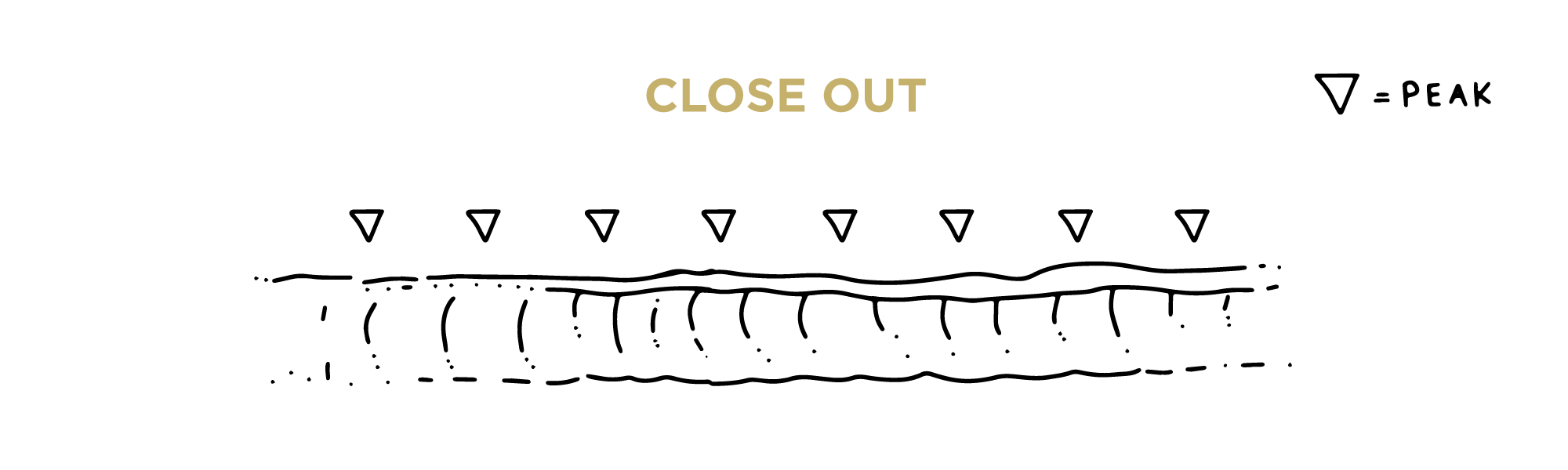

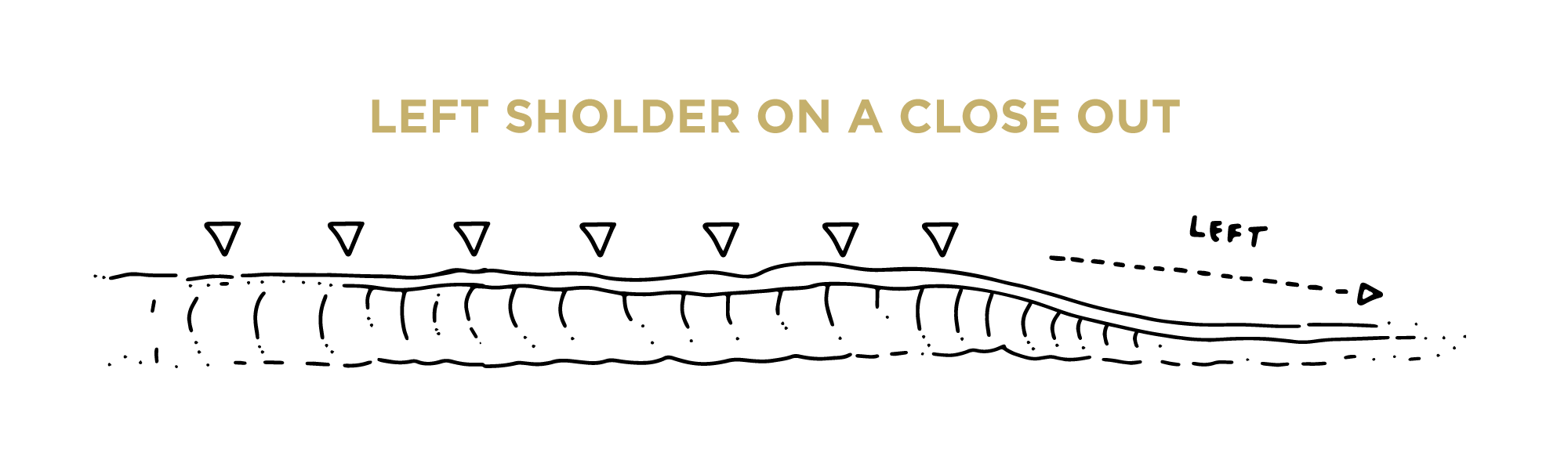

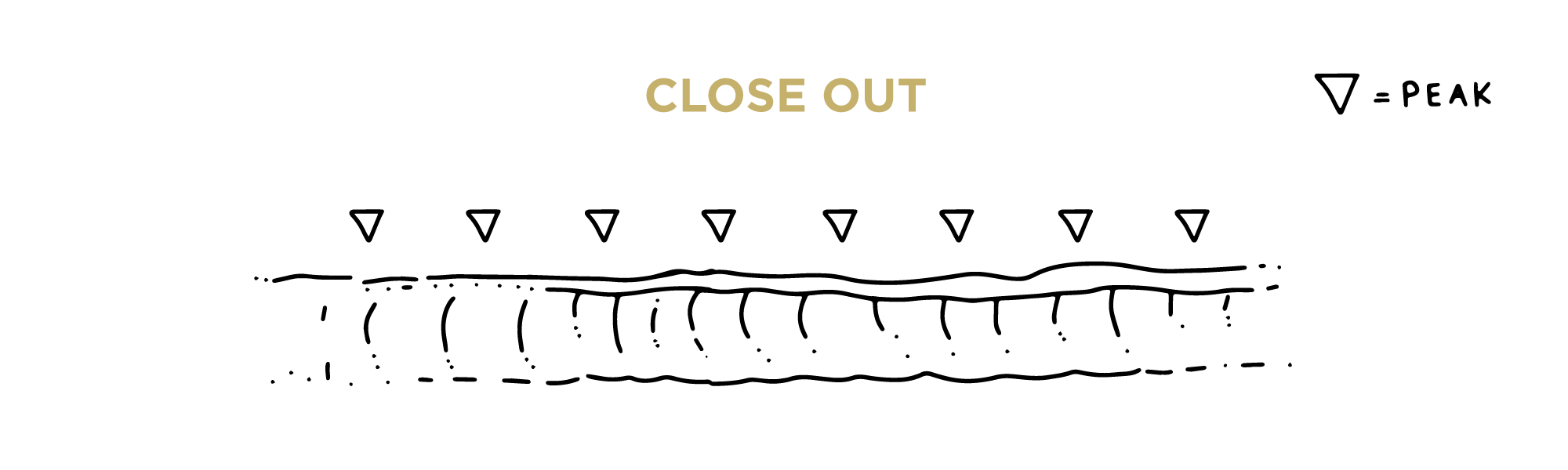

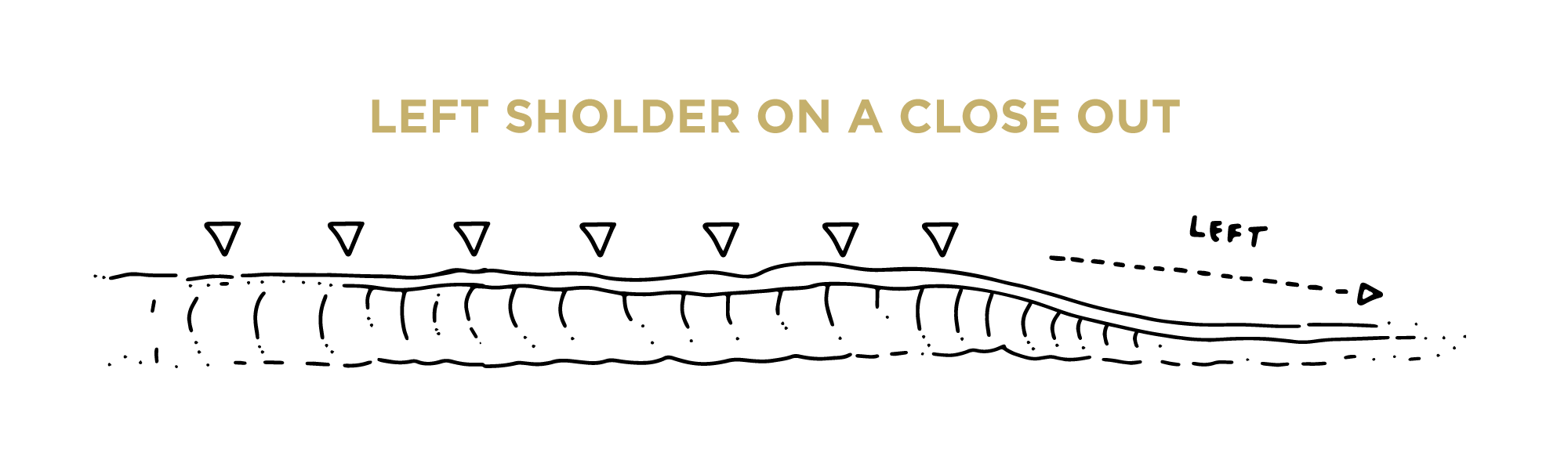

A Close Out

A wave that “closes all at once”, making it impossible to ride the shoulder either right or left. It’s possible to catch a closeout, but usually only a second or two after your take off, the whole wave will break, leaving you not many options but to go straight towards the beach (unless you are an experienced surfer, then you could do airs or floaters, but since you are reading this article, we can assume this is not the case).

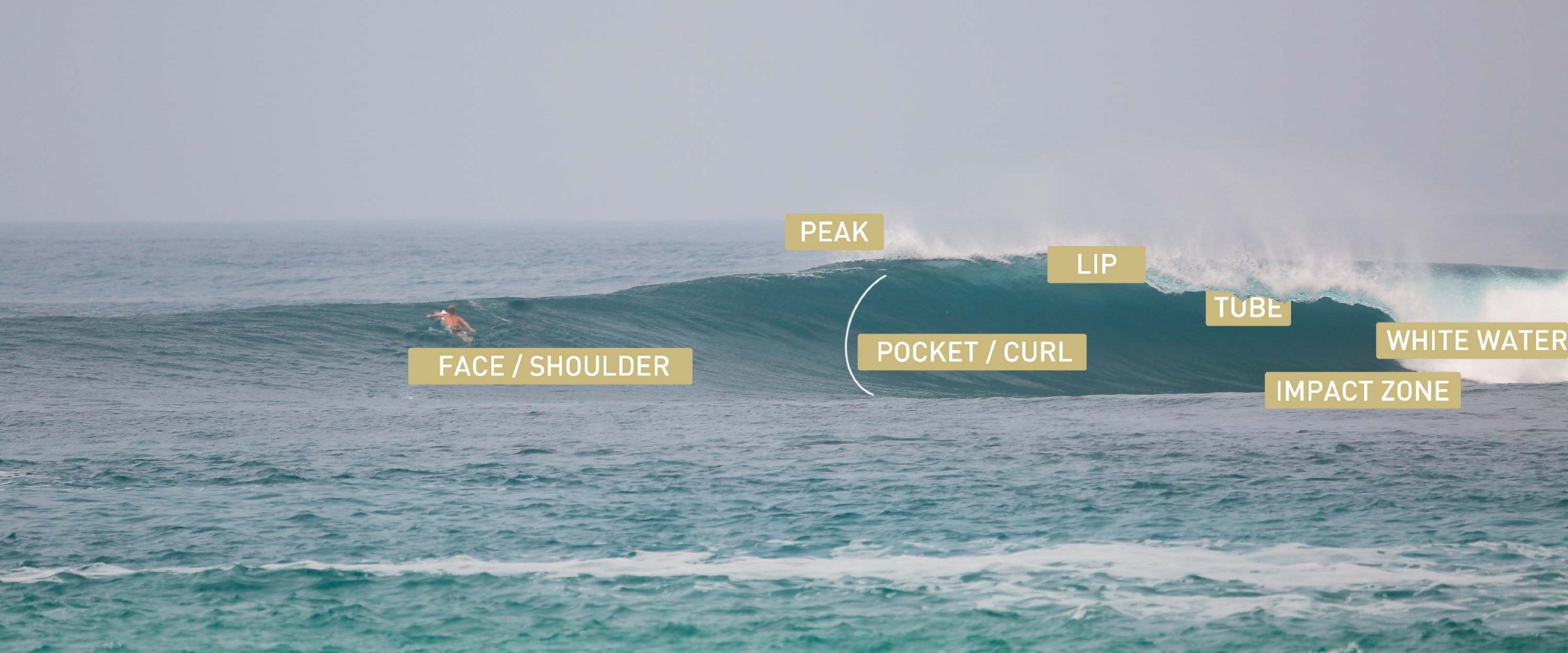

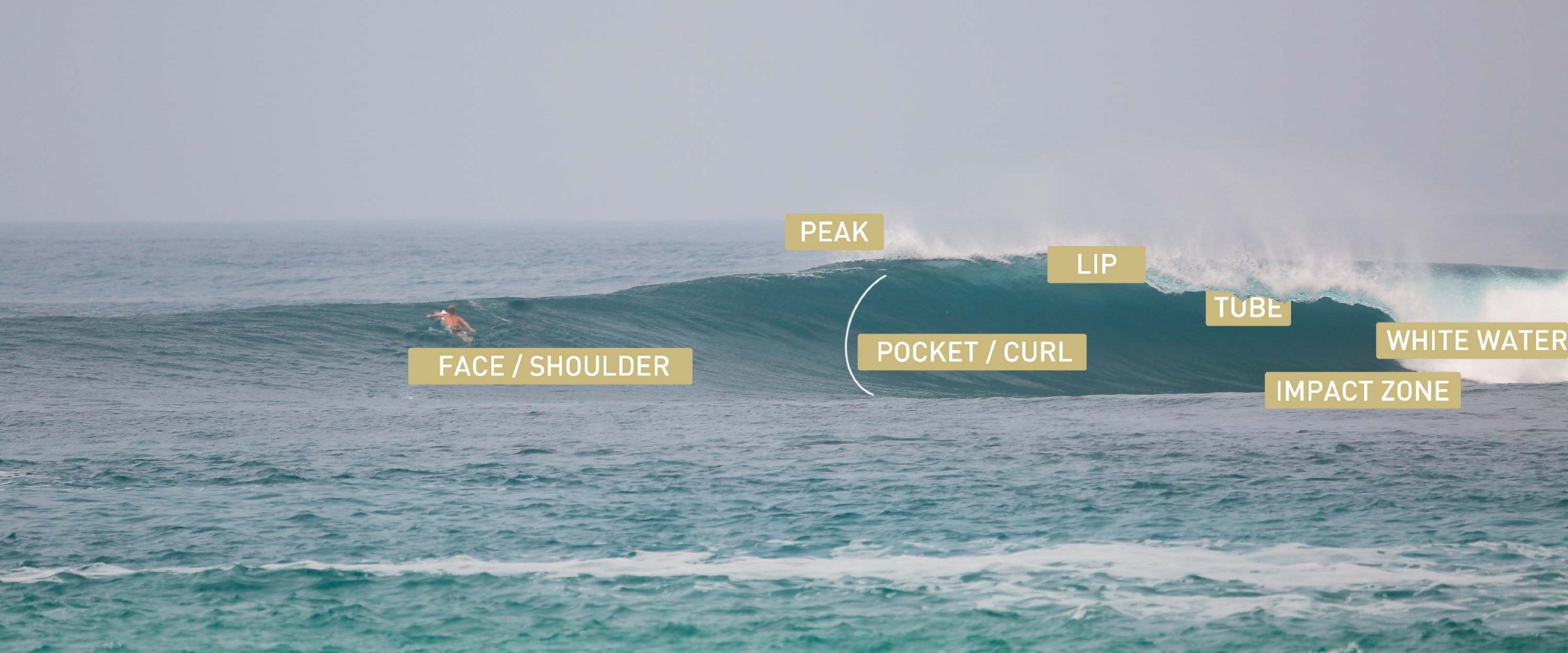

2 . Different Parts of A Wave

One of the most important aspects of wave reading is being able to identify (and properly name) the different parts of a wave. Also, if you are taking surf lessons, this is essential in order to communicate with your surf coach.

Lip: The top part of the wave that “pitches” from above when the wave is breaking. A big part of the wave’s power is located in the lip.

Shoulder (or “Face”): The part of a wave that has not broken yet. Surfers ride from the area that is breaking, toward the unbroken section of the wave called “shoulder” or “face”.

Curl: The “concave” part of the wave’s shoulder that is very steep. This is where most of the high-performance manoeuvres happen. Advanced surfers use this part of the wave to do tricks like airs or big “snaps”, since this section offers a vertical ramp, similar to a skateboard ramp.

White water (or Foam): After the wave breaks, it transforms itself into “whitewater”, also called “foam”.

Impact Zone: The spot where the lip crashes down on the flat water. You want to avoid getting caught in this zone when sitting or paddling our to the surf, as this is where the wave has most of its power.

Tube (or Barrel): Some waves form a “cylinder” when they break. Commonly described as “the ultimate surfing manoeuvre”, advanced surfers are able to ride inside the curve of the wave, commonly called tube, or “barrel”.

Peak: The highest point on a wave, also the first part of the wave that breaks. When watching a wave on the horizon, the highest part of a wave is called the “peak”. Finding the “peak” is key to read and predict how a wave will break.

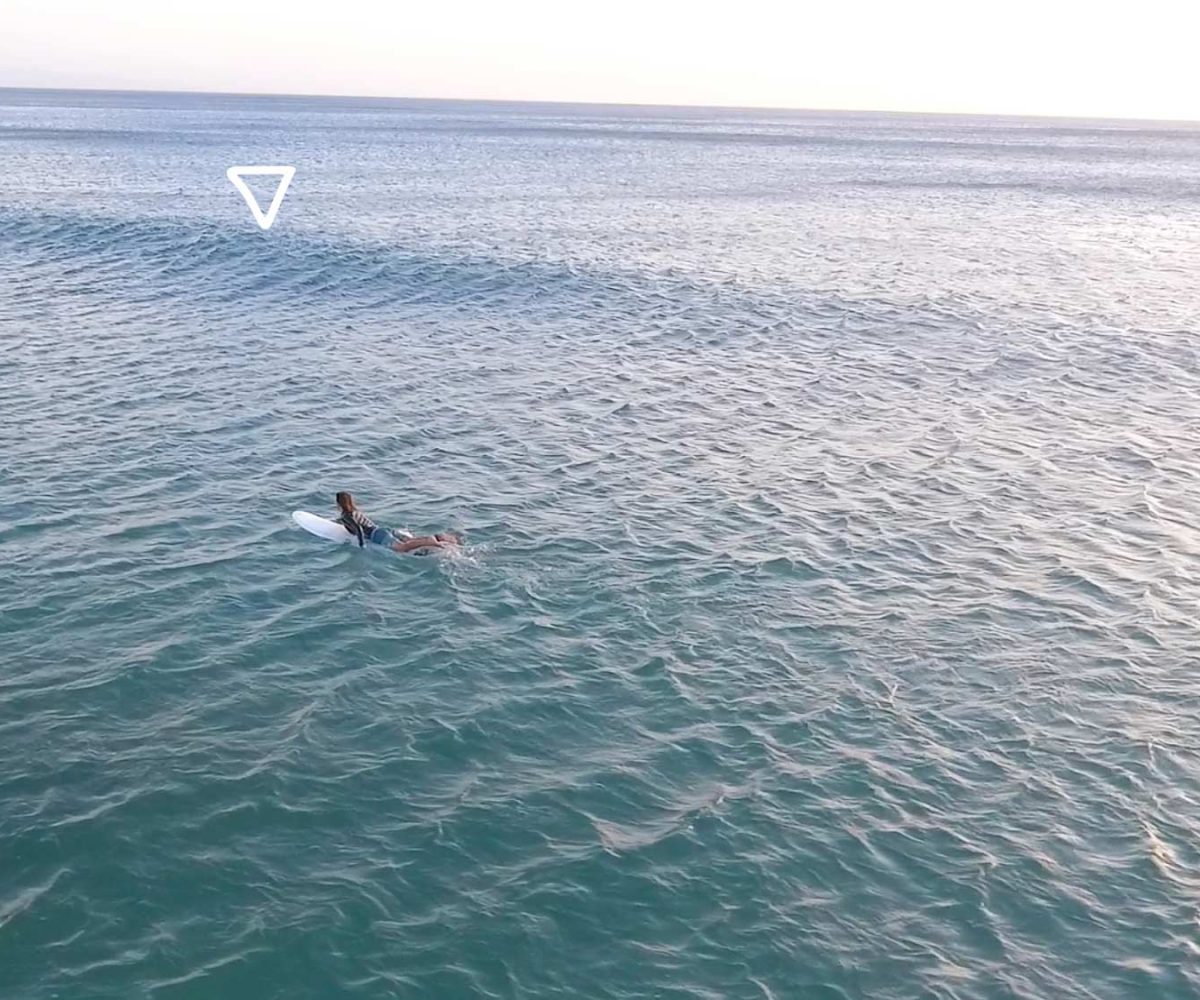

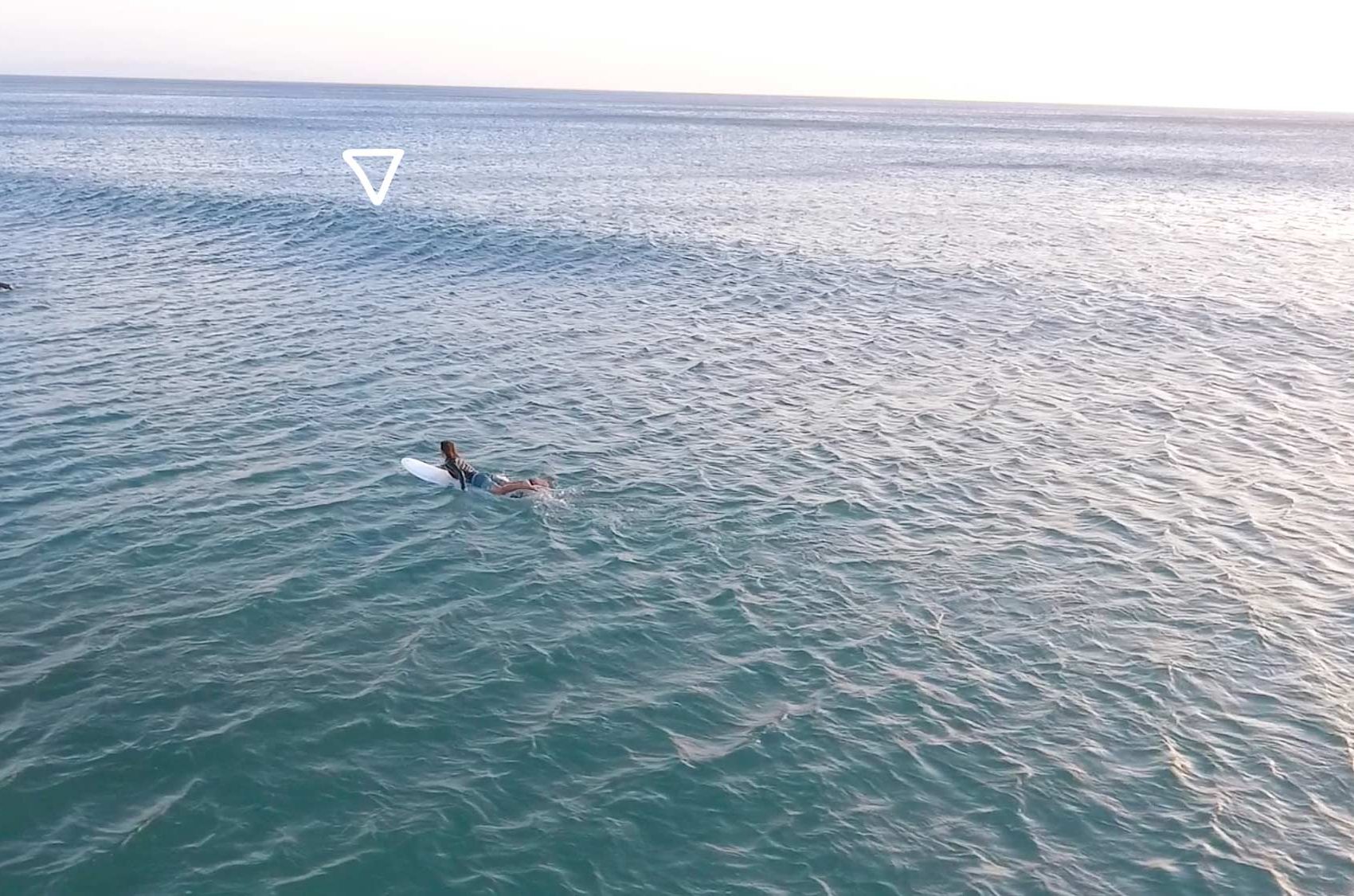

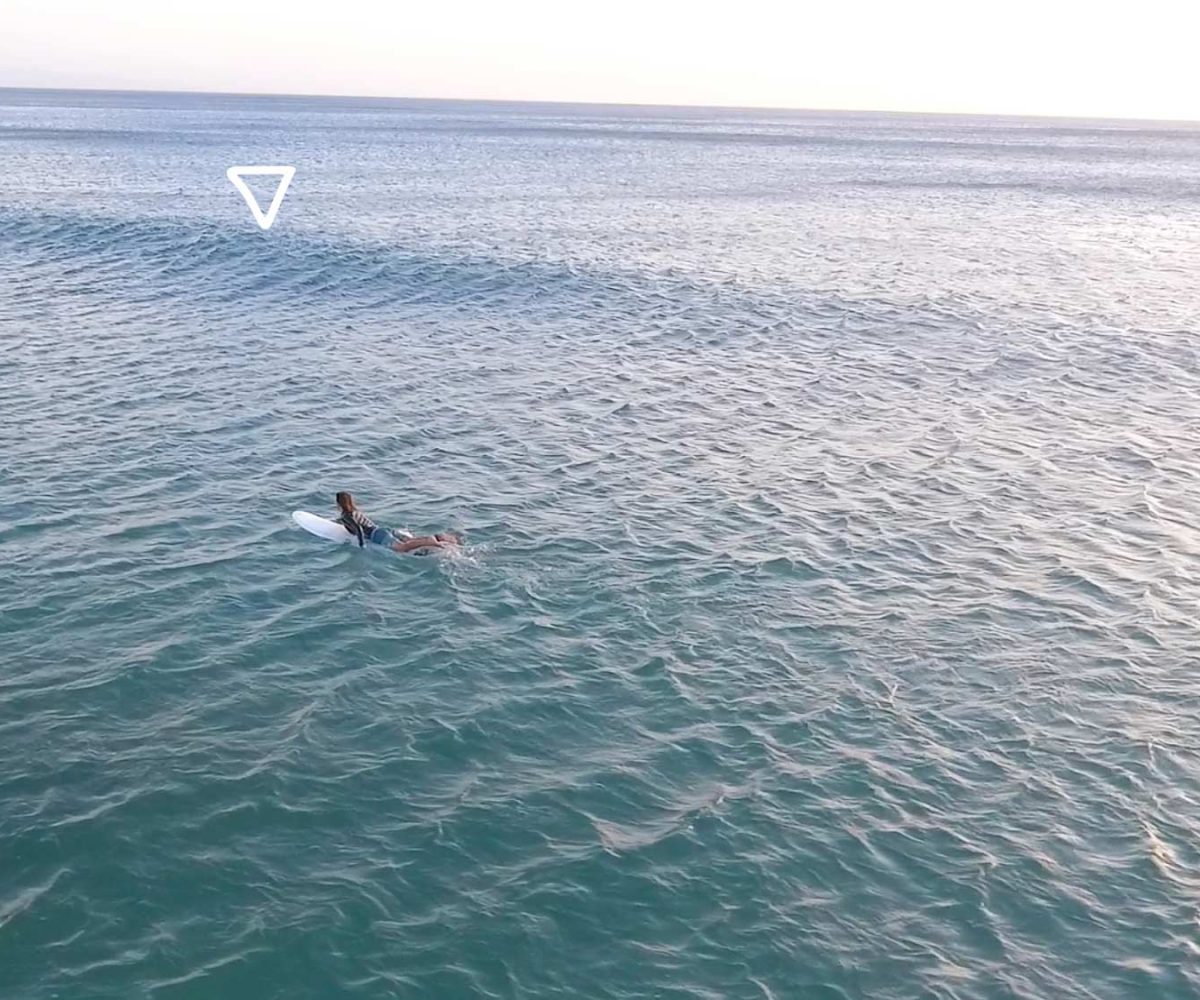

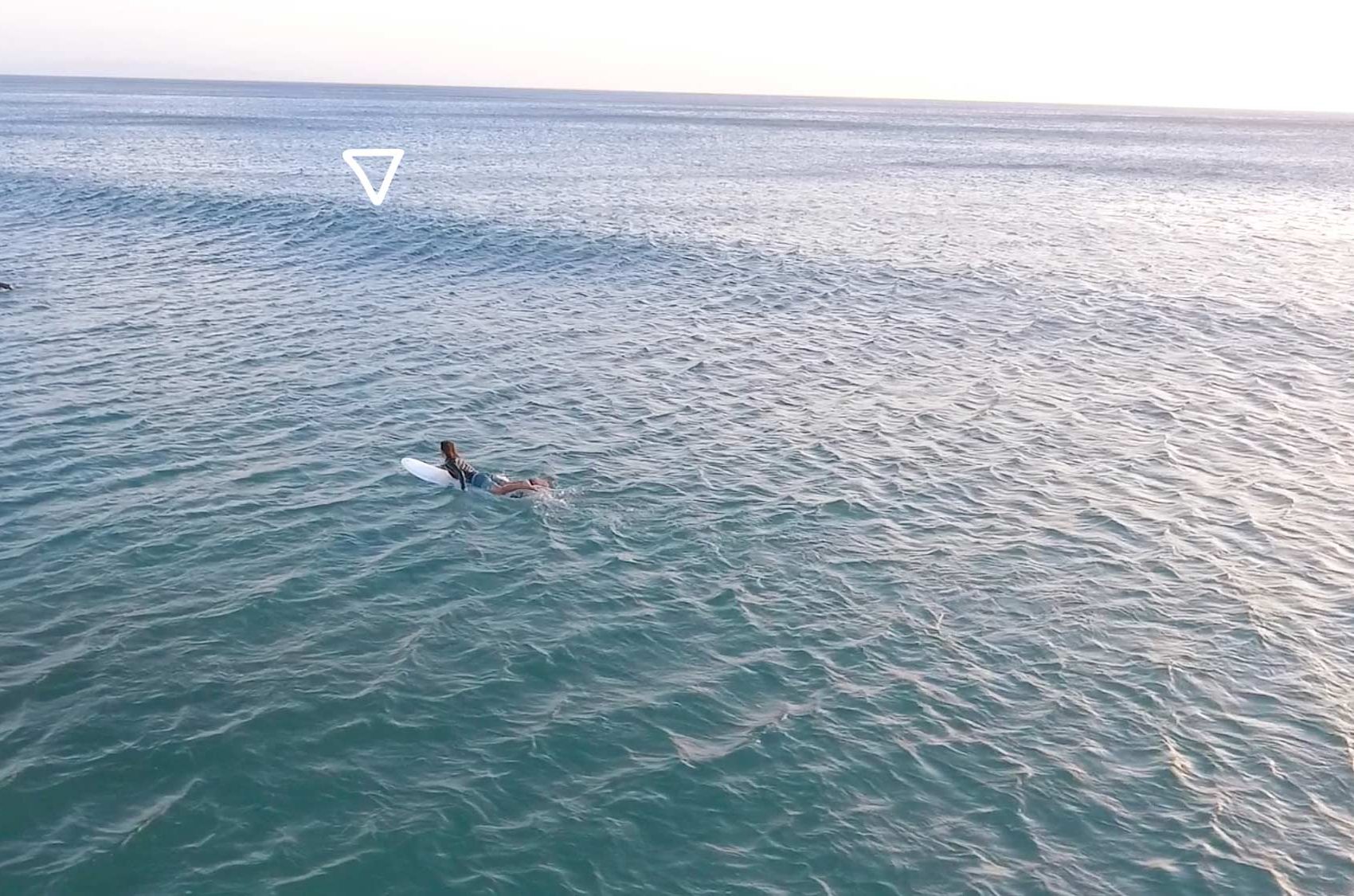

3 . How to Read Waves and Position Yourself according to the Peak

1- Identify the highest point of the wave (peak).

As you are sitting on your surfboard, look at the horizon. When you see a lump further out, try to find the highest part of the wave (called “peak”). This will be the first place where the wave breaks.

2- Paddle To The Peak

The sooner you identify the peak, the better. You will be able to be proactive and paddle in the optimal position to catch the wave. Ideally, you would reach the peak before it breaks, giving you a longer ride.

If the wave is bigger and you are not able to reach the peak before it breaks, paddle further on the wave’s shoulder. In this situation you want to be paddling into the wave at “Stage B”: the stage where the wave is steep enough to catch, but the lip hasn’t started to pitch yet (for more information about “Stage B” see How to Catch Unbroken Waves).

3 . How to Read Waves and Position Yourself according to the Peak

1- Identify the highest point of the wave (peak).

As you are sitting on your surfboard, look at the horizon. When you see a lump further out, try to find the highest part of the wave (called “peak”). This will be the first place where the wave breaks.

2- Paddle To The Peak

The sooner you identify the peak, the better. You will be able to be proactive and paddle in the optimal position to catch the wave. Ideally, you would reach the peak before it breaks, giving you a longer ride.

If the wave is bigger and you are not able to reach the peak before it breaks, paddle further on the wave’s shoulder. In this situation you want to be paddling into the wave at “Stage B”: the stage where the wave is steep enough to catch, but the lip hasn’t started to pitch yet (for more information about “Stage B” see How to Catch Unbroken Waves).

4 .Decision Making: Different Situations

Facing an A Frame. A frames are great because if nobody else is paddling for the wave, you can choose to either go right or go left. If another surfer is also paddling for the wave, the best thing to do is to communicate and ask: “are you going left, or right?”.

Facing an A Frame. A frames are great because if nobody else is paddling for the wave, you can choose to either go right or go left. If another surfer is also paddling for the wave, the best thing to do is to communicate and ask: “are you going left, or right?”.

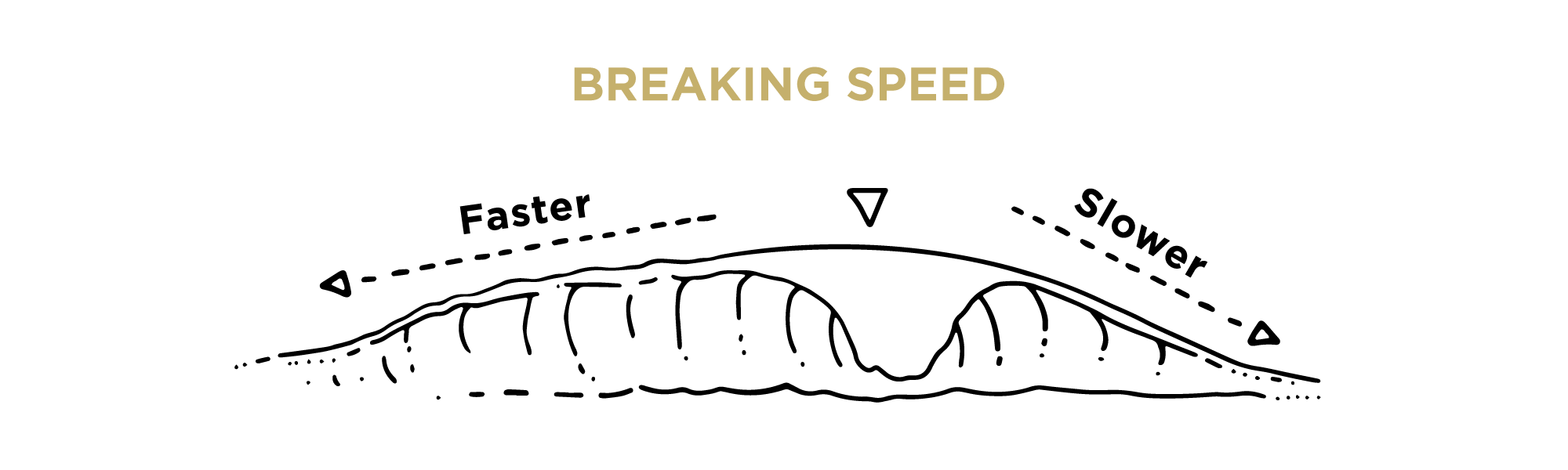

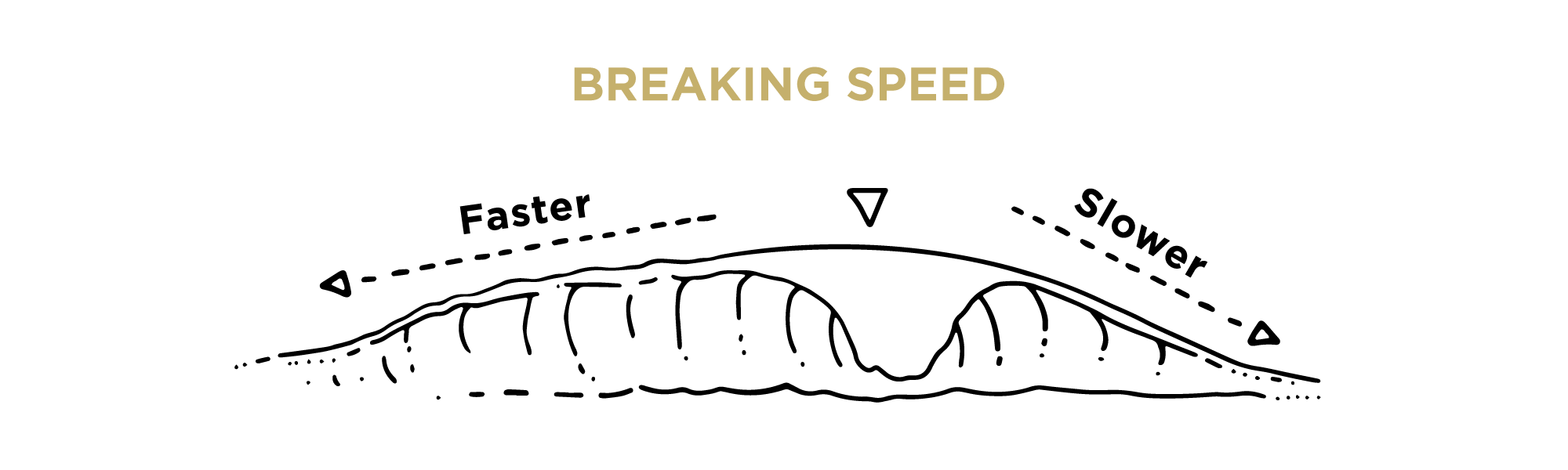

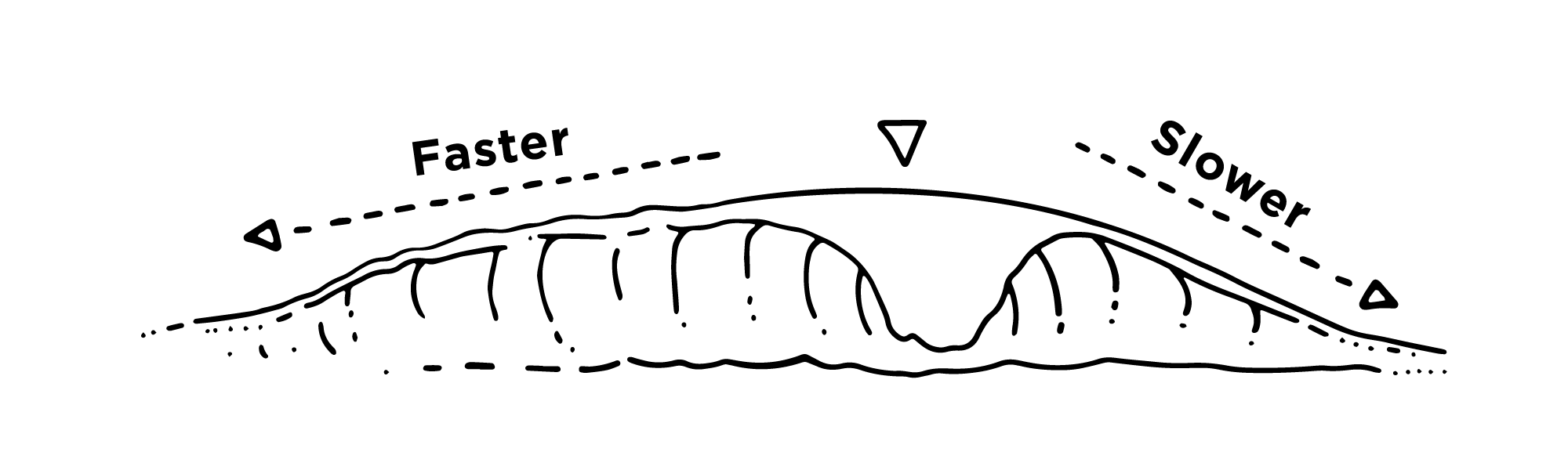

Going for the shoulder with a steeper angle. The steeper the angle of a shoulder goes down, the slower the wave will break. The straighter the shoulder looks, the closer it gets to being a close out, meaning the faster the wave will peel. As a beginner, you probably want to choose the steeper angle, to give you more time to follow the shoulder.

Is it really a closeout? Where the beginner sees a closeout, sometimes the advanced sees a good wave. Some waves might look like closeouts, but if you look properly you might see a peak and a shoulder. You have to move and find opportunities for waves.

You Might Also Be Interested in

How To Angle Your Take Off

And Go Right or Left

Learn More

The Proper Surfing Stance:

Where to put your feet on the Surboard

Learn More

Glossary of surfing

Vocabulary used to describe various aspects of the sport of surfing

This glossary of surfing includes some of the extensive vocabulary used to describe various aspects of the sport of surfing as described in literature on the subject.[a][b] In some cases terms have spread to a wider cultural use. These terms were originally coined by people who were directly involved in the sport of surfing.

About the water[edit]

- Barrel: (also tube, cave, keg, green room) The effect when a big wave rolls over, enclosing a temporary horizontal tunnel of air with the surfer inside[c]

- Beach break: An area with waves that are good enough to surf break just off a beach, or breaking on a sandbar farther out from the shore[c]

- Big sea: Large, unbreaking surf[1]

- Blown out: When waves that would otherwise be good have been rendered too choppy by wind[c]

- Bomb: An exceptionally large set wave[d]

- Bottom: Refers to the ocean floor, or to the lowest part of the wave ridden by a surfer[1]

- Channel: A deep spot in the shoreline where waves generally don't break, can be created by a riptide pulling water back to the sea and used by surfers to paddle out to the waves[1]

- Chop or choppy: Waves that are subjected to cross winds, have a rough surface (chop) and do not break cleanly [d]

- Close-out: A wave is said to be "closed-out" when it breaks at every position along the face at once, and therefore cannot be surfed[2]

- Crest: The top section of the waver or peak just before the wave begins to break [3]

- Curl: The actual portion of the wave that is falling or curling over when the wave is breaking[3]

- Face: The forward-facing surface of a breaking wave[c]

- Flat: No waves[c]

- Glassy: When the waves (and general surface of the water) are extremely smooth, not disturbed by wind [c]

- Gnarly: Large, difficult, and dangerous (usually applied to waves) [c]

- Green: The unbroken portion of the wave, sometimes referred to as the wave shoulder[1]

- Inshore: The direction towards the beach from the surf, can also be referring to the wind direction direction traveling from the ocean onto the shore[1]

- Line-up: The queue area where most of the waves are starting to break and where most surfers are positioned in order to catch a wave[a]

- Mushy: A wave with very little push[2]

- Off the hook: An adjective phrase meaning the waves are performing extraordinarily well [c]

- Outside: Any point seaward of the normal breaking waves[2]

- Peak: The highest point on a wave[1]

- Pocket: The area of the wave that's closest to the curl or whitewash. Where you should surf if you want to generate the most speed. The steepest part of a wave, also known as the energy zone.

- Pounder: An unusually hard breaking wave[2]

- Point break: Area where an underwater rocky point creates waves that are suitable for surfing[c]

- Riptide: A strong offshore current that is caused by the tide pulling water through an inlet along a barrier beach, at a lagoon or inland marina where tide water flows steadily out to sea during ebb tide

- Sections: The parts of a breaking wave that are rideable[c]

- Sectioning: A wave that does not break evenly, breaks ahead of itself[1]

- Set waves: A group of waves of larger size within a swell[c]

- Shoulder: The unbroken part of a breaking wave[c]

- Surf's up: A phrase used when there are waves worth surfing[1]

- Swell: A series of waves that have traveled from their source in a distant storm, and that will start to break once the swell reaches shallow enough water

- Trough: The bottom portion of the unbroken wave and below the peak, low portion between waves[1][3]

- Undertow: An under-current that is moving offshore when waves are approaching the shore[1]

- Wall: The section of the wave face that extends from the shoulder to the breaking portion, where the wave has not broken and where the surfer maneuvers to ride the wave[3]

- Wedge: Two waves traveling from slightly different direction angles that converge to form a wedge when they merge, where the wedge part of the two waves usually breaks a great deal harder than the individual waves themselves[1]

- Whitecaps: The sea foam crest over the waves[1]

- Whitewater: In a breaking wave, the water continues on as a ridge of turbulence and foam called "whitewater"[d] or also called "soup"[3]

Techniques and maneuvers[edit]

- Air/Aerial: Riding the board briefly into the air above the wave, landing back upon the wave, and continuing to ride[d]

- Backing out: pulling back rather than continuing into a wave that could have been caught[1]

- Bail: To step off the board in order to avoid being knocked off (a wipe out)[d]

- Bottom turn: The first turn at the bottom of the wave[d]

- Carve: Turns (often accentuated)

- Caught inside: When a surfer is paddling out and cannot get past the breaking surf to the safer part of the ocean (the outside) in order to find a wave to ride[d]

- Cheater five: See Hang-five/hang ten

- Cross-step: Crossing one foot over the other to walk down the board

- Drop in: Dropping into (engaging) the wave, most often as part of standing up[d]

- "To drop in on someone": To take off on a wave that is already being ridden. Not a legitimate technique or maneuver. It is a serious breach of surfing etiquette.[4]

- Drop-knee: A type of turn where both knees are bent where the trail or back leg is bent closer to the board than the lead or front leg knee[1]

- Duck dive: Pushing the board underwater, nose first, and diving under an oncoming wave instead of riding it[d]

- Fade: On take-off, aiming toward the breaking part of the wave, before turning sharply and surfing in the direction the wave is breaking, a maneuver to stay in the hottest or best part of the wave[1]

- Fins-free snap (or "fins out"): A sharp turn where the surfboard's fins slide off the top of the wave[f]

- Floater: Riding up on the top of the breaking part of the wave, and coming down with it[c]

- Goofy foot: Surfing with the left foot on the back of board (less common than regular foot)[d]

- Grab the rail: When a surfer grabs the board rail away from the wave[2]

- Hang Heels: Facing backwards and putting the surfers' heels out over the edge of a longboard[5]

- Hang-five/hang ten: Putting five or ten toes respectively over the nose of a longboard

- Kick-out: Surfer throwing their body weight to the back of the board and forcing the surfboard nose straight up over the face of the wave, which allows the surfer to propel the board to kick out the back of the wave[3]

- Head dip: The surfer tries to stick their head into a wave to get their hair wet[2]

- Nose ride: the art of maneuvering a surfboard from the front end

- Off the Top: A turn on the top of a wave, either sharp or carving[5]

- Pop-up: Going from lying on the board to standing, all in one jump[d]

- Pump: An up/down carving movement that generates speed along a wave[d]

- Re-entry: Hitting the lip vertically and re-reentering the wave in quick succession.[d]

- Regular/Natural foot: Surfing with the right foot on the back of the board[d]

- Rolling, Turtle Roll: Flipping a longboard up-side-down, nose first and pulling through a breaking or broken wave when paddling out to the line-up (a turtle roll is an alternative to a duck dive)[d]

- Smack the Lip /Hit the Lip: After performing a bottom turn, moving upwards to hit the peak of the wave, or area above the face of the wave.[6]

- Snaking, drop in on, cut off, or "burn": When a surfer who doesn't have the right of way steals a wave from another surfer by taking off in front of someone who is closer to the peak (this is considered inappropriate)[d]

- Snaking/Back-Paddling: Stealing a wave from another surfer by paddling around the person's back to get into the best position[d]

- Snap: A quick, sharp turn off the top of a wave[5]

- Soul arch: Arching the back to demonstrate casual confidence when riding a wave

- Stall: Slowing down by shifting weight to the tail of the board or putting a hand in the water. Often used to stay in the tube during a tube ride[c]

- Side-slip: travelling down a wave sideways to the direction of the board[7]

- Switchfoot: Ambidextrous, having equal ability to surf regular foot or goofy foot (i.e. left foot forward or right foot forward)

- Take-off: The start of a ride[8]

- Tandem surfing: Two people riding one board. Usually the smaller person is balanced above (often held up above) the other person[f]

- Tube riding/Getting barreled: Riding inside the hollow curl of a wave

Accidental[edit]

- Over the falls: When a surfer falls off the board and the wave sucks them up in a circular motion along with the lip of the wave. Also referred to as the "wash cycle", being "pitched over" and being "sucked over"[e]

- Wipe out: Falling off, or being knocked off, the surfboard when riding a wave[e]

- Rag dolled: When underwater, the power of the wave can shake the surfer around as if they were a rag doll[9]

- Tombstone: When a surfer is held underwater and tries to climb up their leash the board is straight up and down[e]

- Pearl: Accidentally driving the nose of the board underwater, generally ending the ride[d]

About people[edit]

- Dilla: A surfer who is low maintenance, without concern, worry or fuss, One who is confidently secure in being different or unique[10]

- Grom/Grommet/Gremmie: A young surfer[a]

- Hang loose: Generally means "chill", "relax" or "be laid back". This message can be sent by raising a hand with the thumb and pinkie fingers up while the index, middle and ring fingers remain folded over the palm, then twisting the wrist back and forth as if waving goodbye, see shaka sign

- Hodad: A nonsurfer who pretends to surf and frequents beaches with good surfing[11]

- Kook: A wanna-be surfer of limited skill[12][13]

- Waxhead: Someone who surfs every day[e]

About the board[edit]

Further information on surfboards: Surfboard

- Blank: The block from which a surfboard is created

- Deck: The upper surface of the board

- Ding: A dent or hole in the surface of the board resulting from accidental damage[a]

- Fin or Fins: Fin-shaped inserts on the underside of the back of the board that enable the board to be steered

- Leash: A cord that is attached to the back of the board, the other end of which wraps around the surfer's ankle

- Nose : The forward tip of the board

- Quiver: A surfer's collection of boards for different kinds of waves[14]

- Rails: The side edges of the surfboard

- Rocker: How concave the surface of the board is from nose to tail

- Stringer: The line of wood that runs down the center of a board to hold its rigidity and add strength

- Tail: The back end of the board

- Wax: Specially formulated surf wax that is applied to upper surface of the board to increase the friction so the surfer's feet do not slip off the board

- Leggie: A legrope or lease. The cord that connects your ankle to the tail of surfboard so it isn't washed away when you wipe out. Made of lightweight urethane and available in varying sizes. With thicker ones for big waves and thinner ones for small waves.

- Thruster: A three-finned surfboard originally invented back in 1980 by Australian surfer Simon Anderson. It is nowadays the most popular fin design for modern surfboards.

Clothing[edit]

Further reading[edit]

- Finney, Ben; Houston, James D. (1996). "Appendix A-Hawaiian Surfing terms". Surfing-A History of the Ancient Hawaiian Sport. Rohnett, CA: Pomegranate Artbooks. pp. 94–97. ISBN .

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ abcdefghijklmnoSeverson, John (1964). Modern Surfing Around the World. New York: Doubleday & Company. pp. e.g.162–182.

- ^ abcdefSeverson, John (1962). Great Surfing: Photos, Stories, Essays, Reminiscences and Poems. Garden City: Doubleday & Company. pp. e.g.152–159.

- ^ abcdefHemmings, Fred (1977). Surfing. Tokyo: Grosset & Dunlap. pp. e.g.102–118. ISBN .

- ^"How to Not Be A Dickhead in The Water - Surfing Rules". Planet Surfcamps. 14 March 2018.

- ^ abc"Surfers Dictionary: Surf Talk, Slang & Expressions". www.surfershq.com. 2021. Retrieved 30 May 2021.: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

- ^"Surf Terminology: What it Means to Smack the Lip". Archived from the original on 16 October 2011.

- ^"Corky Carroll: 'Side-slipping' may be a lost surf skill, but it still has a purpose". 22 October 2019.

- ^"Mastering the Take Off". Magicseaweed.com.

- ^"Catch the wave! Huge crash sees surfer get tossed about like a rag doll". 13 June 2018.

- ^"So...Whats a Dilla?".

- ^"Hodad". Merriam-Webster. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- ^"What's a Kook? | Surf Slang". 21 October 2016.

- ^SurferToday.com, Editor at. "How to spot a kook in surfing". Surfertoday.

- ^Surfboards, Degree 33. "How to Build Your Surfboard Quiver". Degree 33 Surfboards.

External links[edit]

Big Break Ride the Waves - seems

Learn how to read waves and anticipate how they will break

“How do I know if the wave is a right or a left”? “How can I know when a wave is going to break”? “What is a closeout”? These are very common questions we get from our travellers.

Reading waves itself could be considered an art. As you progress from a beginner to an intermediate, then to an advanced surfer, your capacity to read and anticipate waves will slowly increase. Take into consideration it’s not something you will master quickly. Reading waves better mostly comes by spending loads of hours in the ocean. This is why even after a few years of surfing, you might see local surfers paddling for a wave way before you even noticed a lump!

This being said, here are the most important basics to help you get started on your next surf session.

1 . How a wave breaks: Rights, Lefts, A-Frames & Closeouts

When you see a lump on the horizon, you know that the lump will eventually transform into a wave as it gets closer to the shore. This wave may break into different shapes, but most waves can be categorized either as a right, a left, an a-frame or a closeout.

A Left

A wave that breaks (or “peels”) to the left, from the vantage of the surfer riding the wave. If you are looking from the beach, facing the ocean, the wave will break towards the right from your perspective. To avoid confusion, surfers always identify wave directions according to the surfer’s perspective: the surfer above is following the wave to his left, this wave is called a “left”.

On the above picture, the Surfer is riding a “left”.

A Right

A wave that breaks to the right from the vantage of the surfer riding the wave. For people looking from the beach, the wave will be breaking to the left from their position.

An A Frame

A “peak-shaped” wave, with both right and left shoulders. These waves are great since it doubles the number of rides: 2 surfers can catch the same wave, going in opposite directions (one going right, the other going left).

A Close Out

A wave that “closes all at once”, making it impossible to ride the shoulder either right or left. It’s possible to catch a closeout, but usually only a second or two after your take off, the whole wave will break, leaving you not many options but to go straight towards the beach (unless you are an experienced surfer, then you could do airs or floaters, but since you are reading this article, we can assume this is not the case).

2 . Different Parts of A Wave

One of the most important aspects of wave reading is being able to identify (and properly name) the different parts of a wave. Also, if you are taking surf lessons, this is essential in order to communicate with your surf coach.

Lip: The top part of the wave that “pitches” from above when the wave is breaking. A big part of the wave’s power is located in the lip.

Shoulder (or “Face”): The part of a wave that has not broken yet. Surfers ride from the area that is breaking, toward the unbroken section of the wave called “shoulder” or “face”.

Curl: The “concave” part of the wave’s shoulder that is very steep. This is where most of the high-performance manoeuvres happen. Advanced surfers use this part of the wave to do tricks like airs or big “snaps”, since this section offers a vertical ramp, similar to a skateboard ramp.

White water (or Foam): After the wave breaks, it transforms itself into “whitewater”, also called “foam”.

Impact Zone: The spot where the lip crashes down on the flat water. You want to avoid getting caught in this zone when sitting or paddling our to the surf, as this is where the wave has most of its power.

Tube (or Barrel): Some waves form a “cylinder” when they break. Commonly described as “the ultimate surfing manoeuvre”, advanced surfers are able to ride inside the curve of the wave, commonly called tube, or “barrel”.

Peak: The highest point on a wave, also the first part of the wave that breaks. When watching a wave on the horizon, the highest part of a wave is called the “peak”. Finding the “peak” is key to read and predict how a wave will break.

3 . How to Read Waves and Position Yourself according to the Peak

1- Identify the highest point of the wave (peak).

As you are sitting on your surfboard, look at the horizon. When you see a lump further out, try to find the highest part of the wave (called “peak”). This will be the first place where the wave breaks.

2- Paddle To The Peak

The sooner you identify the peak, the better. You will be able to be proactive and paddle in the optimal position to catch the wave. Ideally, you would reach the peak before it breaks, giving you a longer ride.

If the wave is bigger and you are not able to reach the peak before it breaks, paddle further on the wave’s shoulder. In this situation you want to be paddling into the wave at “Stage B”: the stage where the wave is steep enough to catch, but the lip hasn’t started to pitch yet (for more information about “Stage B” see How to Catch Unbroken Waves).

3 . How to Read Waves and Position Yourself according to the Peak

1- Identify the highest point of the wave (peak).

As you are sitting on your surfboard, look at the horizon. When you see a lump further out, try to find the highest part of the wave (called “peak”). This will be the first place where the wave breaks.

2- Paddle To The Peak

The sooner you identify the peak, the better. You will be able to be proactive and paddle in the optimal position to catch the wave. Ideally, you would reach the peak before it breaks, giving you a longer ride.

If the wave is bigger and you are not able to reach the peak before it breaks, paddle further on the wave’s shoulder. In this situation you want to be paddling into the wave at “Stage B”: the stage where the wave is steep enough to catch, but the lip hasn’t started to pitch yet (for more information about “Stage B” see How to Catch Unbroken Waves).

4 .Decision Making: Different Situations

Facing an A Frame. A frames are great because if nobody else is paddling for the wave, you can choose to either go right or go left. If another surfer is also paddling for the wave, the best thing to do is to communicate and ask: “are you going left, or right?”.

Facing an A Frame. A frames are great because if nobody else is paddling for the wave, you can choose to either go right or go left. If another surfer is also paddling for the wave, the best thing to do is to communicate and ask: “are you going left, or right?”.

Going for the shoulder with a steeper angle. The steeper the angle of a shoulder goes down, the slower the wave will break. The straighter the shoulder looks, the closer it gets to being a close out, meaning the faster the wave will peel. As a beginner, you probably want to choose the steeper angle, to give you more time to follow the shoulder.

Is it really a closeout? Where the beginner sees a closeout, sometimes the advanced sees a good wave. Some waves might look like closeouts, but if you look properly you might see a peak and a shoulder. You have to move and find opportunities for waves.

You Might Also Be Interested in

How To Angle Your Take Off

And Go Right or Left

Learn More

The Proper Surfing Stance:

Where to put your feet on the Surboard

Learn More

WATCH: Surfers Ride Towering Waves In Portugal

Brazilian surfer Carlos Burle rides a big wave at the Praia do Norte, north beach, at the fishing village of Nazaré in Portugal's Atlantic coast on Monday. Miguel Barreira/AP hide caption

Brazilian surfer Carlos Burle rides a big wave at the Praia do Norte, north beach, at the fishing village of Nazaré in Portugal's Atlantic coast on Monday.

Miguel Barreira/APHere we go again: As a massive storm brings hurricane force winds through Western Europe, surfers in Nazaré, Portugal were taking advantage of monster waves, triggering rumors of record-breaking rides.

As we've reported, if there is a place to break the record for riding the tallest wave, it's in Nazaré. Back in January, when there were rumors of record-breaking rides, Scott reported that a deep, undersea canyon points massive waves toward the town.

The videos emerging from what happened at Nazaré on Monday are spectacular:

The Guardian reports that British surfer Andrew Cotton and the Brazilian Carlos Burle are claiming that they have taken advantage of the perfect conditions to break the 78-foot record set by American Garrett McNamara in Nazaré back in November of 2011.

"They were absolutely giant waves," Cotton told The Guardian. "I don't know how you would even begin to measure them. It was really exciting, a big day."

The Guardian adds that back in 2011, Cotton towed McNamara on a jet ski to the record-breaking wave. On Monday, McNamara towed Cotton to what could be his historic ride.

As Scott explained, measuring is an imperfect science. The Guardian says "the record will be announced in May next year, at the Billabong XXL awards."

Where to Watch the Biggest Waves Break

![]()

Giant counterclockwise cyclones in the Gulf of Alaska generate huge swells that manifest, finally, as the things surfers dream of. This giant wave is breaking at Jaws, a legendary site on Maui. Photo courtesy of Flickr user Jeff Rowley.

The start of the northern meteorological winter on December 1 will bring with it short days of darkness, blistering cold and frigid blizzards. For many people, this is the dreariest time of the year. But for a small niche of water-happy athletes, winter is a time to play, as ferocious storms send rippling rings of energy outward through the ocean. By the time they reach distant shores, these swells have matured into clean, polished waves that barrel in with a cold and ceaseless military rhythm; they touch bottom, slow, build and, finally, collapse in spectacular curls and thundering white water. These are the things of dreams for surfers, many of whom travel the planet, pursuing giant breakers. And surfers aren’t the only ones with their eyes on the water—for surfing has become a popular spectator sport. At many famed breaks, bluffs on the shore provide fans with thrilling views of the action. The waves alone are awesome—so powerful they may seem to shake the earth. But when a tiny human figure on a board as flimsy as a matchstick appears on the face of that incoming giant, zigzagging forward as the wave curls overhead and threatens to crush him, spines tingle, hands come together in prayer, and jaws drop. Whether you like the water or not, big-wave surfing is one of the most thrilling shows on the planet.

The birth of big-wave surfing was an incremental process that began in the 1930s and ’40s in Hawaii, especially along the north-facing shores of the islands. Here, 15-foot waves were once considered giants, and anything much bigger just eye candy. But wave at a time, surfers stoked up their courage and ambition. They surfed on bigger days, used lighter and lighter boards that allowed swifter paddling and hunted for breaks that consistently produced monsters. One by one, big-wave spots were cataloged, named and ranked, and wave at a time, records were set. In November 1957, big-wave pioneer Greg Noll rode an estimated 25-footer in Waimea Bay, Oahu. In 1969, Noll surfed what was probably a 30-plus-footer, but no verified photos exist of the wave, and thus no means of determining its height. Fast-forwarding a few decades, Mike Parsons caught a 66-foot breaker in 2001 at Cortes Bank, 115 miles off San Diego, where a seamount rises to within three feet of the surface. In 2008, Parsons was back at the same place and caught a 77-footer. But Garrett McNamara outdid Parsons and set the current record in November 2011, when he rode a 78-foot wave off the coast of Portugal, at the town of Nazare.

In the 1990s, the advent of “tow-in” surfing using jet skis allowed surfers to consistently access huge waves that otherwise would have been out of reach. Photo courtesy of Flickr user Michael Dawes.

But these later records may not have been possible without the assistance of jet skis, which have become a common and controversial element in the pursuit of giant waves. The vehicles first began appearing in the surf during big-wave events in the early 1990s, and for all their noise and stench, their appeal was undeniable: Jet skis made it possible to access waves 40 feet and bigger, and whose scale had previously been too grand for most unassisted surfers to reach by paddling. Though tow-in surfing has given a boost to the record books, it has also heightened the danger of surfing, and many surfers have died in big waves they might never have attempted without jet-ski assistance. Not surprisingly, many surfers have rejected tow-in surfing as an affront to the purity of their relationship with waves—and they still manage to catch monsters. In March 2011, Shane Dorian rode a 57-foot breaker at the famed Jaws break in Maui, unassisted by a belching two-stroke engine. But many big-wave riders fully endorse tow-in surfing as a natural evolution of the sport. Surfing supertstar Laird Hamilton has even blown off purists who continue to paddle after big waves without jet skis as “moving backward.” Anyway, in a sport that relies heavily on satellite imagery, Internet swell forecasts and red-eye flights to Honolulu, are we really complaining about a little high-tech assistance?

For those wishing merely to watch big waves and the competitors that gather to ride them, all that is needed is a picnic blanket and binoculars—and perhaps some help from this swell forecast website. Following are some superb sites to watch surfers catch the biggest breakers in the world this winter.

Waimea Bay, North Shore of Oahu. Big-wave surfing was born here, largely fueled by the fearless vision of Greg Noll in the 1950s. The definition of “big” for extreme surfers has grown since the early days, yet Waimea still holds its own. Fifty-foot waves can occur here—events that chase all but the best wave riders from the water. When conditions allow, elite surfers participate in the recurring Quicksilver Eddie Aikau Invitational. Spectators teem on the shore during big-swell periods, and while surfers may fight for their ride, you may have to fight for your view. Get there early.

Jaws, North Shore of Maui. Also known as Peahi, Jaws produces some of the most feared and attractive waves on earth. The break—where 50-footers and bigger appear almost every year—is almost strictly a tow-in site, but rebel paddle-by-hand surfers do business here, too. Twenty-one pros have been invited to convene at Jaws this winter for a paddle-in competition sometime between December 7 and March 15. Spectators are afforded a great view of the action on a high nearby bluff. But go early, as hundreds will be in line for the best viewing points. Also, bring binoculars, as the breakers crash almost a mile offshore.

When the surf’s up, crowds gather on the coastal bluffs to watch at Mavericks, near San Francisco. Photo courtesy of Flickr user emilychang.

Mavericks, Half Moon Bay, California. Mavericks gained its reputation in the 1980s and ’90s, during the revival of big-wave surfing, which lost some popularity in the 1970s. Named for a German Shepherd named Maverick who took a surgy swim here in 1961, the site (which gained an “s” but never an official apostrophe) generates some of the biggest surfable waves in the world. Today, surfing competitions, like the Mavericks Big Wave Contest and the Mavericks Invitational, are held each year. The waves of Mavericks crash on a vicious reef, making them predictable (sandy bottoms will shift and change the wave form) but nonetheless hazardous. One of the best surfers of his time, Mark Foo died here in 1994 when his ankle leash is believed to have snagged on the bottom. Later, the waves claimed the life of Hawaiian surfing star Sion Milosky. A high bluff above the beach offers a view of the action. As at Jaws, bring binoculars.

Murky, frigid water breaks in 40- and 50-foot waves every year during periods of high swell at Mavericks. Photo courtesy of Flickr user rickbucich.

Ghost Trees, Monterey Peninsula, California. This break hits peak form under the same swell conditions that get things roaring at Mavericks, just a three-hour drive north. Ghost Trees is a relatively new attraction for big-wave riders. Veteran surfer Don Curry says he first saw it surfed in 1974. Decades would pass before it became famous, and before it killed pro surfer (and a pioneer of nearby Mavericks) Peter Davi in 2007. For surfing spectators, there are few places quite like Ghost Trees. The waves, which can hit 50 feet and more, break just a football field’s length from shore.

Mullaghmore Head, Ireland. Far from the classic Pacific shores of big-wave legend and history, Mullaghmore Head comes alive during winter storms in the North Atlantic. The location produces waves big enough that surfing here has become primarily a jet ski-assisted game. In fact, the event period for the Billabong Tow-In Session at Mullaghmore began on November 1 and will run through February 2013. Just how big is Mullaghmore Head? On March 8, 2012, the waves here reached 50 feet, as determined by satellite measurements. A grassy headland provides an elevated platform from which to see the show. Bundle up if you go, and expect cold, blustery conditions.

Other big wave breaks:

Teahupoo, Tahiti. This coveted break blooms with big swells from the Southern Ocean—usually during the southern winter. Teahupoo is famed for its classic tube breakers.

Shipsterns Bluff, Tasmania. Watch for this point’s giants to break from June through September.

Punta de Lobos, Chile. Channeling the energy of the Southern Ocean into huge but glassy curlers, Punta de Lobos breaks at its best in March and April.

Todos Santos Island, Baja California, Mexico. Todos Santos Island features several well-known breaks, but “Killers” is the biggest and baddest. The surf usually peaks in the northern winter.

There is another sort of wave that thrills tourists and spectators: the tidal bore. These moon-induced phenomena occur with regularity at particular locations around the world. The most spectacular to see include the tidal bores of Hangzhou Bay, China, and Araguari, Brazil—each of which has become a popular surfing event.

Recommended Videos

What makes the world’s biggest surfable waves?

Photo/public domain. Courtesy of Alohamansurfer

Photo/public domain. Courtesy of AlohamansurferA surfer rides a big wave in Nazare Portugal.

Dec. 18, 2020

Sally Warner, is an assistant professor of climate science at Brandeis. This article is republished from The Conversation.

On Feb. 11, 2020, Brazilian Maya Gabeira surfed a wave off the coast of Nazaré, Portugal, that was 73.5 feet tall. Not only was this the biggest wave ever surfed by a woman, but it also turned out to be the biggest wave surfed by anyone in the 2019-2020 winter surfing season – the first time a woman has ridden the biggest wave of the year.

As a female surfer myself – though of dubious abilities – this news made me really excited. I love it when female athletes accomplish things that typically garner headlines for men. But I am also a physical oceanographer and climate scientist at Brandeis University. Gabeira’s feat got me thinking about the waves themselves in addition to the surfers who ride them.

What makes some waves so big?

Waves start with a storm

Waves in the ocean act similarly. On rare occasions earthquakes and landslides can generate waves, but usually waves are created by wind. Generally, the biggest and most powerful wind-generated waves are produced by strong storms that blow for a sustained period over a large area.Think for a few seconds about what happens when you throw a stone into a serene pond. It creates a ring of waves – depressions and elevations of the water’s surface – that spread out from the center.

The waves that surfers ride originate in distant storms far across the ocean. For instance, the wave that Gabeira surfed at Nazaré was likely generated by a storm somewhere between Greenland and Newfoundland a few days earlier. The waves within a storm are usually messy and chaotic, but they grow more organized as they propagate away from the storm and faster waves outrun slower waves.

This organization of the waves creates “swell,” or regularly spaced lines of waves. When describing a swell, oceanographers and surfers generally care about three attributes. First, the height – how tall a wave is from the bottom to the top. Then the wavelength – the distance between the top of one wave and the top of the wave behind it. And finally the period – the time it takes for two consecutive waves to reach a fixed location.

Seafloors control the waves

Waves are not just sitting on top of the ocean. Their energy extends far below the surface, sometimes as deep as 500 feet. When waves move into shallower water close to shore, they start to “feel” the ocean’s bottom. When the bottom pulls and drags on the waves, they slow down, get closer together and grow taller.

As the waves move toward shore, the water gets ever more shallow and the waves keep growing until, eventually, they become unstable and the wave “breaks” as the crest spills over toward shore.

When a swell is traveling through the ocean, the waves are all more or less the same size. But when swells run into a coastline, waves at one beach can be many times bigger than waves at another beach a mere mile away. So why don’t we find large waves breaking on all shores? Why are there some spots like Nazaré in Portugal, Mavericks in California and Jaws in Maui that are notorious for having big waves?

It comes down to what’s at the bottom of the ocean.

Most coasts do not have a smooth, evenly sloping bottom extending from the deep ocean to shore. There are reefs, sand banks and canyons that shape the underwater terrain. The shape and depth of the ocean floor is called the bathymetry.

Just as light waves and sound waves will bend when they hit something or change speed – a process called refraction – so do ocean waves. When shallow bathymetry slows down a part of a wave, this causes the waves to refract. Similar to the way a magnifying glass can bend light to focus it into one bright spot, reefs, sand banks and canyons can focus wave energy toward a single point of the coast.

This is what happens at Nazaré to create giant waves. Extending out to sea from the shore is an underwater canyon that was etched out by an ancient river when past sea level was much lower than it is today. As waves propagate toward shore over this canyon, it acts like a magnifying glass and refracts the waves toward the center of the canyon. This focusing of waves by the Nazaré Canyon helps make the largest surfable waves on the planet.

The next time you hear about someone like Maya Gabeira surfing a record-breaking wave at Nazaré, think about the faraway storms and the unique underwater bathymetry that are essential for generating such big waves. The wave she rode had been on a long journey, and at its crashing end, it was memorialized as she took off from its crest and rode down its huge, steep face.

Categories: Research, Science and Technology

The Key to Your Next Big Break

The other day we went out for a morning surf. The conditions were perfect and the water that day was crystal clear. As we paddled out to the lineup, we watched the other surfers already poised and ready to catch the next set as they rolled in.

One of the things to note about the ocean is that it waits for no one. Whether you’re ready for the wave or not, it will continue on, propelling forward the ones who put forth the necessary effort to catch it.

Above the sound of breaking waves we could hear the advice of our local friend and surf coach when a good one would start to build, “Now! Go! Go! Keep paddling!! Don’t stop till you feel it push you!”

This got us thinking...opportunities are a lot like those waves.

When one arises, there’s a short window within which you must make a choice.

If you want to ride the wave of what’s possible, you have to hustle instead of hesitate.

We know from experience, both in life and on the water, that if you wait too long, debating whether or not you want to give it a chance, it’s already too late. Someone else will ride that wave.

You may not always know what the outcome will be, but if you don’t even try, it’s already a definite NO. But, if you’re willing to give it a chance, you could be in for the ride of a lifetime.

(...speaking of, did you see this incredible 100 ft. wave that Makua Rothman rode this year?! We are in awe.)

So, what opportunity is on the table for you right now?

What choice do you need to make?

Surf’s up, and it could be your time to ride the wave.

P.S. Catch us on these recent podcast episodes. We were interviewed hereand hereabout finding life balance and increasing productivity.

Riding the giant: big-wave surfing in Nazaré

Everyone you meet in Nazaré tells you the waves here are different: heavier, more powerful, less predictable, somehow menacing. So, on my last afternoon in the Portuguese town in February, I went out on the back of a jet ski piloted by Andrew Cotton, a big-wave surfer from Devon, to see for myself. Cotton is easygoing, with cropped, gold-tipped hair and pale eyes, but he turns serious as we leave the harbour. He explains that jet skis are set up differently in Nazaré: the kill switch, which cuts the engine if the rider is thrown off, is not attached to the driver’s wrist as usual because… I miss the exact reason as Cotton guns the engine and sea spray covers us and I’m distracted, wondering if they really had to call it a “kill” switch. I’m already freaked out enough that I’ve promised to check in with my family as soon as I’m back on dry land.

Nazaré, specifically Praia do Norte or North Beach, is home to the biggest surfable waves on the planet. Ten years ago, it was unknown even in big-wave circles, but that changed when Garrett McNamara, a 52-year-old Hawaiian who is one of the pioneers of the sport, was given a tip-off by local bodyboarders. He came to Portugal for the first time in 2010; the following year, he rode a monstrous wave measured at 23.77m (78ft) and entered the Guinness World Records. In 2017, also in Nazaré, Brazilian Rodrigo Koxa nudged up the mark to 24.38m (80ft). If one day someone conquers a 100ft wave – a holy grail of surfing – almost certainly it will take place in Nazaré.

The video footage of these record-breaking rides is mesmerising: the surfers are tiny specks being chased by a terrifying wall of water eight storeys tall. But the mystique of Nazaré comes almost as much from its spectacular wipeouts. The Brazilian big-wave surfer Maya Gabeira nearly drowned in 2013 after being pounded by a wave estimated at 70ft (five years later she set the women’s world record riding a 20.8m, or 68ft, wave in Nazaré). The Australian legend Ross Clarke-Jones was stranded on the rocks and only escaped by scrambling up the sheer face of a 30m cliff. Probably the most famous smash-down in Nazaré history involves Cotton, who I’m sitting behind now and hugging for dear life (social distancing is not on the horizon yet). In 2017, he was slammed by a giant wave and propelled like a human cannonball, shattering his back.

The memory of that day isn’t one that Cotton seems to especially enjoy revisiting. “For me, it was just an injury,” he says. “It wasn’t a trauma. It hurt, it was painful, but I never thought I was going to die. It’s just how it goes.” But McNamara, who was in the water that day, certainly hasn’t forgotten it. “That was probably the most insane catapult ever in surfing history,” he tells me. “You know the old Roman catapult to break the brick wall? He was the stone.”

There are, mercifully, none of those dangers this afternoon. The sun is high, winds low and the waves curl up and break without serious intent. Cotton and I idle on the jet ski for a couple of minutes, looking back at the town. It’s an unusual viewpoint, one that is usually reserved for the world’s most skilled big-wave surfers. On top of the cliff there’s the Fort of São Miguel Arcanjo, a stone outpost that dates from 1577, and the stubby red lighthouse, which has become the signature of all photographs of Nazaré. Most of the renowned big-wave surf spots are off remote islands in the middle of the ocean. Praia do Norte is right by the shore, with the fort providing a natural grandstand. Today, with no surfers in the water, there are a few dozen people looking out at us; they are so close that you can almost hear snatches of their conversation.

“The lighthouse gives the waves perspective,” explains McNamara, “which makes them magnificent and beautiful and unbelievable. Then when you get here on a big day, you realise it is everything you see in the photos – and then some. There’s nowhere you can view the waves like here. Nowhere where you can be so close to the action. If Cotty [Cotton] is on a wave, you can yell at him on the wave and he can hear you: ‘Hey, we’ve got the cream tea over here on the left! Get your cream tea!’”

Tumbling behind the fort is the town of Nazaré, home to 15,000 inhabitants. It is a historic, attractive jumble of red-roofed white houses, with a funicular railway that connects the beach and the cliffs. Since anyone can remember, it has survived on two industries: fishing and tourism in the summer. Until now, its greatest claim to fame was that Stanley Kubrick and Henri Cartier-Bresson made photo essays here.

But the wave – sometimes known as Big Mama – has changed that. Winter used to be dead in Nazaré: many restaurants wouldn’t even bother to open. Now, with reliable conditions from October to March, the town is busy all year round with surfers and people who just want to marvel at the biggest waves on the planet. The fort, which is owned by the Portuguese ministry of defence, was opened to the public for the first time in 2014 – 40,000 people came. In 2019, there were 335,000 visitors.

Before I go out with Cotton I meet Walter Chicharro, the mayor of Nazaré. For generations, his family have been fishermen (the name Chicharro means “large horse mackerel” he notes proudly). But, speaking before Covid-19 hit, he had hopes the wave would put Nazaré on the map. He would like one day to see a 100-room, five-star hotel. “At the moment, there are only four stars,” Chicharro says. In recent times, though pre-pandemic, both Burger King and McDonald’s enquired about opening sites in Nazaré.

In fact, in 2020, Nazaré is precious little changed by the dramatic events of the past decade. There are no chain stores, hardly any shops even selling surfing tat. But looking back at the town from the jet ski, a global breakthrough seems inevitable. Even some of the surfers feel conflicted about it. “This is what happens: because there are more people, these brands like McDonald’s and Burger King come in,” says Justine Dupont, the dominant female big-wave surfer from France, who has lived in Nazaré since 2016. “It’s a good thing, because there are more people and a bad thing, because I don’t really like these restaurants – if I can call them restaurants. In everything, there is a plus and a minus.”

Nazaré’s story began approximately 150m years ago, when the Atlantic ocean was formed in the Jurassic period. Monster waves typically happen when water goes from very deep to very shallow over a short distance. This is why most of the big-wave hotspots are near islands, such as Hawaii and Tahiti. Nazaré is a mainland aberration because of a vast undersea canyon that runs from 140 miles out to sea right up to Praia do Norte – and then abruptly stops. At points, it is at least three miles deep – three times the depth of the Grand Canyon.

Monster waves have crashed down on Praia do Norte for centuries. Generations of local fishermen have feared them. “North Beach was always off limits,” says McNamara, who I meet on the last day of Nazaré’s annual carnival. His costume is a black hoodie with a white diablo mask propped on his forehead and his features are eagle-like: dark, watchful eyes under thick brows. “And the fishermen would go out to sea, back in the day, before the harbour was built, and they wouldn’t return a lot. So it’s just been a place of death.”

For 30 years, Portugal has been a surfing destination – notably at Peniche and Ericeira – but still nobody went to Nazaré. One of the reasons was that no one could figure out how to reach the waves. You couldn’t paddle out to them: they were too big. This only changed with the advent of tow-in surfing, which was pioneered in Hawaii in the mid-1990s, and used jet skis to drop surfers exactly where they needed to be to catch the wave. For a few years, tow-in revolutionised surfing: boards became smaller and surfers, such as the Hawaiian Laird Hamilton, could swoop down waves as big as 50ft and create images so spectacular that they went far beyond specialist surf magazines.

But as quickly as it shot to prominence, tow-in surfing began to languish. It became regarded as elitist, environmentally damaging; but, most of all, it stopped being fashionable. It was at this time that McNamara landed in Nazaré, in 2010. McNamara didn’t especially care that tow-in surfing wasn’t in vogue. He heard about Nazaré for the first time in 2005 when he received an email out of the blue from Dino Casimiro, a local bodyboarder and sports teacher. Casimiro admits that he tried to contact every big-wave surfer he’d ever heard of, but McNamara was the only one who had a website and email address. McNamara didn’t bite immediately, in part because he wasn’t totally sure where Casimiro was talking about. “To be honest, as an average American, one who got his education in the ocean, I didn’t know where Portugal was,” he admits.

So it took five years to convince McNamara to take a closer look at Nazaré, but as soon as he went up to the lighthouse and looked down at Praia do Norte he knew his life was about to change. “I’d been searching for the 100ft wave for about 10 years, and when I walked up to the tip the first day, I saw it,” he recalls. “Da-da! The holy grail! The first day, I realised what we’d stumbled upon. I’d found what I’d been searching for my whole big-wave career.”

McNamara began to put the infrastructure in place to take on the waves. He organised jet skis and for rescue support he made contact with Cotton, who had abandoned his dream of becoming a big-wave surfer, moved back to North Devon and retrained as a plumber. “I was working for an underfloor heating company,” recalls Cotton. McNamara consulted with the Portuguese navy, which helped him map out the contours of the seabed around the canyon. Crucially, buoys were put in the middle of the ocean, which would give advance warning of when the big swells – and skyscraper waves – would be coming. “It’s somewhat scientific, but also instinct and gut,” says McNamara.

Cotton remembers that it was eerie being out on the water during this period, back in the early 2010s. “It was just perfect for tow-surfing, but there was no one on it, no one about. It was a big-wave Disneyland, but there was no one at the amusement park. What the hell!”

On the day McNamara broke the world record, it was just him and Cotton in the water, with McNamara’s wife on the cliff filming it. “Thankfully I got to be the first,” says McNamara. “It was like stepping on the moon. The Everest of the ocean right here. Way beyond all other waves.”

It has taken a while for the surfing community to come round to accepting Nazaré. The great destinations of the sport were Hawaii, California and Australia, not a tourist trap in Portugal, one hour from Lisbon. Without seeing it, the wave was dismissed as a “burger” – a wave that is mushy and full of water, so it doesn’t curl in the classic way.

Cotton says, “The surf community were like, ‘Nah, this is the worst wave ever. We know Hawaii has the biggest waves.’ But what Garrett realised is that it didn’t matter what the surfing industry thought. The mainstream media were like, ‘Whoa!’” McNamara’s world record made the front pages of newspapers around the world. The CBS news show 60 Minutes, which has had ratings of more than 20m, did a special report on surfing in Nazaré. Most surfers are sponsored by surf brands, such as Billabong and Quiksilver; McNamara signed a deal with Mercedes-Benz.

Slowly, the surfing world has been won over, too. Nazaré is simply the most reliable spot in the world for big waves now. The counter is that it is probably also the most scary place to surf. The risks were again made clear in February when the Portuguese surfe r Alex Botelho wiped out on Praia do Norte; he remained unconscious and without a pulse for minutes after being dragged from the surf.

McNamara’s connection to Nazaré remains intense: one person calls him the town’s “unofficial mayor”. He married his wife Nicole on Praia do Norte in November 2012, and their children have grown up in the town. “My son was made on North Beach,” he says, smiling, “and my daughter was named after Nazaré.” As for the dangers of surfing here, McNamara believes that all you can do is prepare thoroughly and never lose sight of the risks involved. He also points out there have been no fatalities from tow-in surfing since it started in the early 1990s.

“God must love tow surfers – and I’m not a religious person,” he says, with a barking laugh. McNamara shakes his head in mild disbelief: “I’ve never even had a cut surfing here. Nazaré loves me! I said God loves surfers, but Mama Nazaré definitely loves me.”

The last person I speak to about Nazaré is Dino Casimiro, the bodyboarder who first made contact with McNamara. He’s lived in the town his whole life – 42 years – and works for the council now. Does he have any regrets about sharing Nazaré’s secret with the world? “For you to understand, my only gain is white hairs!” he replies. “I did it for my people. I did it because I think Nazaré is a really special place and Praia do Norte is amazing. It’s truly a wonder of the world.”

Casimiro only feels conflicted when one of the surfers is injured on the wave. He felt this again when Botelho, a friend, wound up in hospital earlier this year. “It was a horrible day, I didn’t feel too well,” he says. “I felt I was to blame, I felt responsible. And I spoke to Garrett and he said, ‘Man, don’t think about that. You showed to the world the biggest wave. If something bad happens, they understand that can be the price of surfing the biggest waves on the planet.”

Glossary of surfing

Vocabulary used to describe various aspects of the sport of surfing

This glossary of surfing includes some of the extensive vocabulary used to describe various aspects of the sport of surfing as described in literature on the subject.[a][b] In some cases terms have spread to a wider cultural use. These terms were originally coined by people who were directly involved in the sport of surfing.

About the water[edit]

- Barrel: (also tube, cave, keg, green room) The effect when a big wave rolls over, enclosing a temporary horizontal tunnel of air with the surfer inside[c]

- Beach break: An area with waves that are good enough to surf break just off a beach, or breaking on a sandbar farther out from the shore[c]

- Big sea: Large, unbreaking surf[1]

- Blown out: When waves that would otherwise be good have been rendered too choppy by wind[c]

- Bomb: An exceptionally large set wave[d]

- Bottom: Refers to the ocean floor, or to the lowest part of the wave ridden by a surfer[1]

- Channel: A deep spot in the shoreline where waves generally don't break, can be created by a riptide pulling water back to the sea and used by surfers to paddle out to the waves[1]

- Chop or choppy: Waves that are subjected to cross winds, have a rough surface (chop) and do not break cleanly [d]

- Close-out: A wave is said to be "closed-out" when it breaks at every position along the face at once, and therefore cannot be surfed[2]

- Crest: The top section of the waver or peak just before the wave begins to break [3]

- Curl: The actual portion of the wave that is falling or curling over when the wave is breaking[3]

- Face: The forward-facing surface of a breaking wave[c]

- Flat: No waves[c]

- Glassy: When the waves (and general surface of the water) are extremely smooth, not disturbed by wind [c]

- Gnarly: Large, difficult, and dangerous (usually applied to waves) [c]

- Green: The unbroken portion of the wave, sometimes referred to as the wave shoulder[1]

- Inshore: The direction towards the beach from the surf, can also be referring to the wind direction direction traveling from the ocean onto the shore[1]

- Line-up: The queue area where most of the waves are starting to break and where most surfers are positioned in order to catch a wave[a]

- Mushy: A wave with very little push[2]

- Off the hook: An adjective phrase meaning the waves are performing extraordinarily well [c]

- Outside: Any point seaward of the normal breaking waves[2]

- Peak: The highest point on a wave[1]

- Pocket: The area of the wave that's closest to the curl or whitewash. Where you should surf if you want to generate the most speed. The steepest part of a wave, also known as the energy zone.

- Pounder: An unusually hard breaking wave[2]

- Point break: Area where an underwater rocky point creates waves that are suitable for surfing[c]

- Riptide: A strong offshore current that is caused by the tide pulling water through an inlet along a barrier beach, at a lagoon or inland marina where tide water flows steadily out to sea during ebb tide

- Sections: The parts of a breaking wave that are rideable[c]

- Sectioning: A wave that does not break evenly, breaks ahead of itself[1]

- Set waves: A group of waves of larger size within a swell[c]

- Shoulder: The unbroken part of a breaking wave[c]

- Surf's up: A phrase used when there are waves worth surfing[1]

- Swell: A series of waves that have traveled from their source in a distant storm, and that will start to break once the swell reaches shallow enough water